The bitcoin blockchain is helping keep a botnet from being taken down

When hackers corral infected computers into a botnet, they take special care to ensure they don’t lose control of the server that sends commands and updates to the compromised devices. The precautions are designed to thwart security defenders who routinely dismantle botnets by taking over the command-and-control server that administers them in a process known as sinkholing.

Recently, a botnet that researchers have been following for about two years began using a new way to prevent command-and-control server takedowns: by camouflaging one of its IP addresses in the bitcoin blockchain.

Impossible to block, censor, or take down

When things are working normally, infected machines will report to the hardwired control server to receive instructions and malware updates. In the event that server gets sinkholed, however, the botnet will find the IP address for the backup server encoded in the bitcoin blockchain, a decentralized ledger that tracks all transactions made using the digital currency.

By having a server the botnet can fall back on, the operators prevent the infected systems from being orphaned. Storing the address in the blockchain ensures it can never be changed, deleted, or blocked, as is sometimes the case when hackers use more traditional backup methods.

“What’s different here is that typically in those cases there’s some centralized authority that’s sitting on the top,” said Chad Seaman, a researcher at Akamai, the content delivery network that made the discovery. “In this case, they’re utilizing a decentralized system. You can’t take it down. You can’t censor it. It’s there.”

Converting Satoshi values

An Internet protocol address is a numerical label that maps the network location of devices connected to the Internet. An IP version 4 address is a 32-bit number that’s stored in four octets. The current IP address for arstechnica.com, for instance, is 18.190.81.75, with each octet separated by a dot. (IPv6 addresses are out of the scope of this post.)

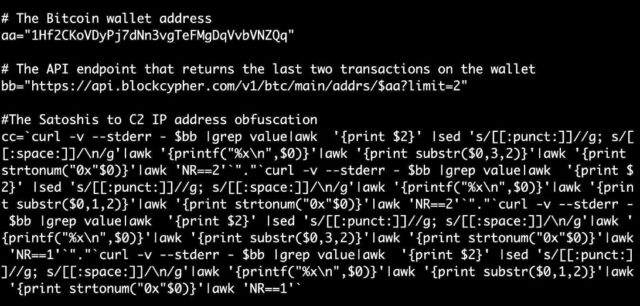

The botnet observed by Akamai stored the backup server IP address in the two most recent transactions posted to 1Hf2CKoVDyPj7dNn3vgTeFMgDqVvbVNZQq, a bitcoin wallet address selected by the operators. The most recent transaction provided the third and fourth octets, while the second most recent transaction provided the first and second octets.

The octets are encoded in the transaction as a “Satoshi value,” which is one hundred millionth of a bitcoin (0.00000001 BTC) and currently the smallest unit of the bitcoin currency that can be recorded on the blockchain. To decode the IP address, the botnet malware converts each Satoshi value into a hexadecimal representation. The representation is then broken up into two bytes, with each one being converted to its corresponding integer.

The image below depicts a portion of a bash script that the malware uses in the conversion process. aa shows the bitcoin wallet address chosen by the operators, bb contains the endpoint that looks up the two most recent transactions, and cc shows the commands that convert the Satoshi values to the IP address of the backup server.

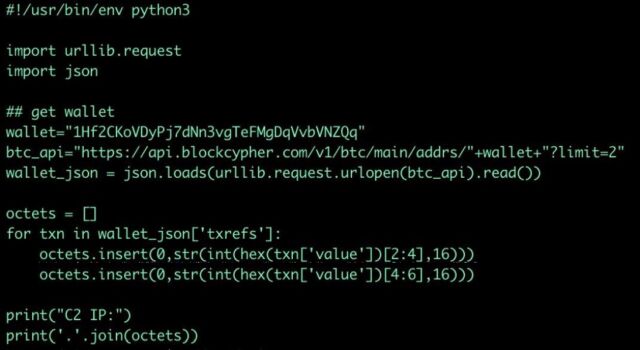

If the script was converted into Python code, it would look like this:

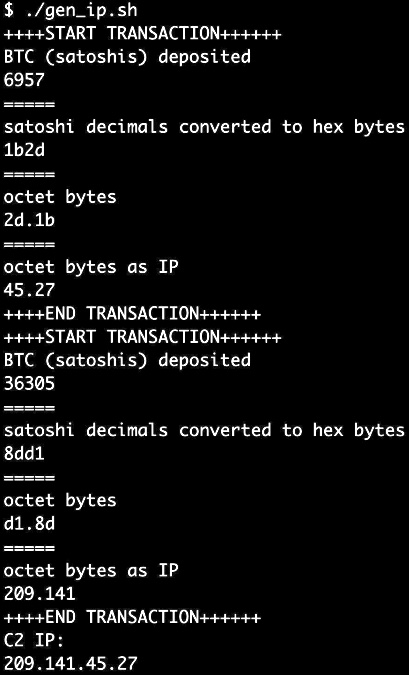

The Satoshi values in the two most recent wallet transactions are 6957 and 36305. When converted, the IP address is: 209.141.45.27

In a blog post being published on Tuesday, Akamai researchers explain it this way:

Knowing this, let’s look at the values of these transactions and convert them into IP address octets. The most recent transaction has a value of 6,957 Satoshis, converting this integer value into its hexadecimal representation results in the value 0x1b2d. Taking the first byte (0x1b) and converting it into an integer results in the number 45—this will be the 3rd octet of our final IP address. Taking the second byte (0x2d) and converting it into an integer results in the number 27, which will become the 4th octet in our final IP address.

The same process is done with the second transaction to obtain the first and second octets of the C2 IP address. In this case, the value of the second transaction is 36,305 Satoshis. This value converted to its hexadecimal representation results in the hex value of 0x8dd1. The first byte (0x8d), and the second byte (0xd1), are then converted into integers. This results in the decimal numbers 141 and 209 which are the second and first octets of the C2 IP address respectively. Putting the four generated octets together in their respective order results in the final C2 IP address of 209.141.45.27.

Here’s a representation of the conversion process:

Not entirely new

While Akamai researchers say they have never before seen a botnet in the wild using a decentralized blockchain to store server addresses, they were able to find this research that demonstrates a fully functional command server built on top of the blockchain for the Ethereum cryptocurrency.

“By leveraging the blockchain as intermediate, the infrastructure is virtually unstoppable, dealing with most of the shortcoming of regular malicious infrastructures,” wrote Omer Zoha, the researcher who devised the proof-of-concept control server lookup.

Criminals already had other covert means for infected bots to locate command servers. For example, VPNFilter, the malware that Russian government-backed hackers used to infect 500,000 home and small office routers in 2018, relied on GPS values stored in images stored on Photobucket.com to locate servers where later-stage payloads were available. In the event the images were removed, VPNFilter used a backup method that was embedded in a server at ToKnowAll.com.

Malware from Turla, another hacking group backed by the Russian government, located its control server using comments posted in Britney Spears’ official Instagram account.

The botnet Akamai analyzed uses the computing resources and electricity supply of infected machines to mine the Monero cryptocurrency. In 2019, researchers from Trend Micro published this detailed writeup on its capabilities. Akamai estimates that, at current Monero prices, the botnet has mined about $43,000 worth of the digital coin.

Cheap to disrupt, costly to restore

In theory, blockchain-based obfuscation of control server addresses can make takedowns much harder. In the case here, disruptions are simple, since sending a single Satoshi to the attacker’s wallet will change the IP address that the botnet malware calculates.

With a Satoshi valued at .0004 cent (at the time of research, anyway), $1 would allow 2,500 disruption transactions to be placed in the wallet. The attackers, meanwhile, would have to deposit 43,262 Satoshis, or about $16.50, to recover control of their botnet.

There’s yet another way to defeat the blockchain-based resilience measure. The fallback measure activates only when the primary control server fails to establish a connection or it returns an HTTP status code other than 200 or 405.

“If sinkhole operators successfully sinkhole the primary infrastructure for these infections, they only need to respond with a 200 status code for all incoming requests to prevent the existing infection from failing over to using the BTC backup IP address,” Akamai researcher Evyatar Saias explained in Tuesday’s post.

“There are improvements that can be made, which we’ve excluded from this write-up to avoid providing pointers and feedback to the botnet developers,” Saias added. “Adoption of this technique could be very problematic, and it will likely gain popularity in the near future.”

Post updated to correct amount of Monero mined and to correct spelling of Saias.