Facebook shuts down hackers who infected iOS and Android devices

Facebook said it has disrupted a hacking operation that used the social media platform to spread iOS and Android malware that spied on Uyghur people from the Xinjiang region of China.

Malware for both mobile OSes had advanced capabilities that could steal just about anything stored on an infected device. The hackers, which researchers have linked to groups working on behalf of the Chinese government, planted the malware on websites frequented by activists, journalists, and dissidents who originally came from Xinjiang and had later moved abroad.

“This activity had the hallmarks of a well-resourced and persistent operation while obfuscating who’s behind it,” Mike Dvilyanski, head of Facebook cyber espionage investigations, and Nathaniel Gleicher, the company’s head of security policy, wrote in a post on Wednesday. “On our platform, this cyber espionage campaign manifested primarily in sending links to malicious websites rather than direct sharing of the malware itself.”

Infecting iPhones for years

The hackers seeded websites with malicious JavaScript that could surreptitiously infect targets’ iPhones with a full-featured malware that Google and security firm Volexity profiled in August 2019 and last April. The hackers exploited a host of iOS vulnerabilities to install the malware, which Volexity called Insomnia. Researchers refer to the hacking group as Earth Empusa, Evil Eye, or PoisonCarp.

Google said that at the time some of the exploits were used, they were zero-days, meaning they were highly valuable because they were unknown to Apple and most other organizations around the world. Those exploits worked against iPhones running iOS versions 10.x, 11.x, and 12.0 and 12.1. Volexity later found exploits that worked against versions 12.3, 12.3.1, and 12.3.2. Taken together, the exploits gave the hackers the ability to infect devices for more than two years. Facebook’s post shows that even after being exposed by researchers, the hackers have remained active.

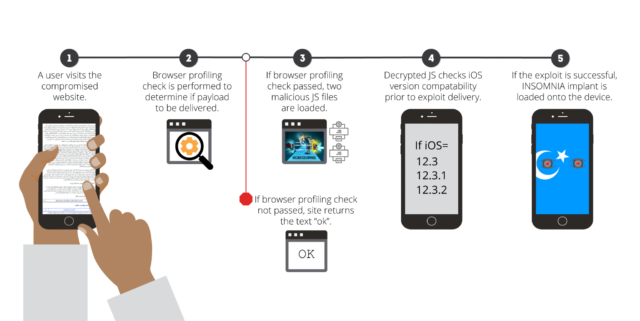

Insomnia had capabilities to exfiltrate data from a host of iOS apps, including contacts, GPS, and iMessage, as well as third-party offerings from Signal, WhatsApp, Telegram, Gmail, and Hangouts. To keep the hacking concealed and prevent the Insomnia from being discovered, the exploits were delivered only to people who passed certain checks, including IP addresses, OSesd, browser, and country and language settings. Volexity provided the following diagram to illustrate the exploit chain that successfully infected iPhones.

A sprawling network

Evil Eye used fake apps to infect Android phones. Some sites mimicked third-party Android app stores that published software with Uyghur themes. Once installed, the trojanized apps infected devices with one of two malware strains, one known as ActionSpy and the other called PluginPhantom.

Facebook also named two China-based companies it said had developed some of the Android malware. “These China-based firms are likely part of a sprawling network of vendors, with varying degrees of operational security,” Facebook’s Dvilyanski and Gleicher wrote.

Officials with the Chinese government have steadfastly denied that it engages in hacking campaigns like the ones reported by Facebook, Volexity, Google, and other organizations.

Unless you have a connection to Uyghur dissidents, it’s unlikely that you’ve been targeted by the operations identified by Facebook and the other organizations. For people who want to check for signs that their devices have been hacked, Wednesday’s post provides indicators of compromise.