Platon: The Man Who’s Far More Than a Photographer

All images by Platon. Used with permission.

“I’m not really a photographer at all,” proclaimed Platon in the opening of his 2017 Netflix documentary. Hearing this left me feeling perplexed. How could someone who had dedicated so much to the craft tell the world he’s not a photographer? Four years later, I was given the opportunity to speak to him. One hour after our conversation started, I understood exactly what he meant. As talented as he is, Platon offers so much more than a man using a camera.

Editor’s Note: This is a special interview. If you wish to listen to it, we invite you to do so in the audio widget below.

As he sat in the comfort of his New York studio, and me in a traditional Colombian home, we conducted the interview in 2021 style: via ZOOM. Very quickly, the dynamic stopped feeling like the other interviews I’ve done. Instead, it felt like two fellas shooting the breeze about photography. Much of that was because of Platon’s demeanour. Despite having photographed some of the world’s most influential people, Platon carries no ego. He treated me like an equal, which set the tone for a fantastic conversation.

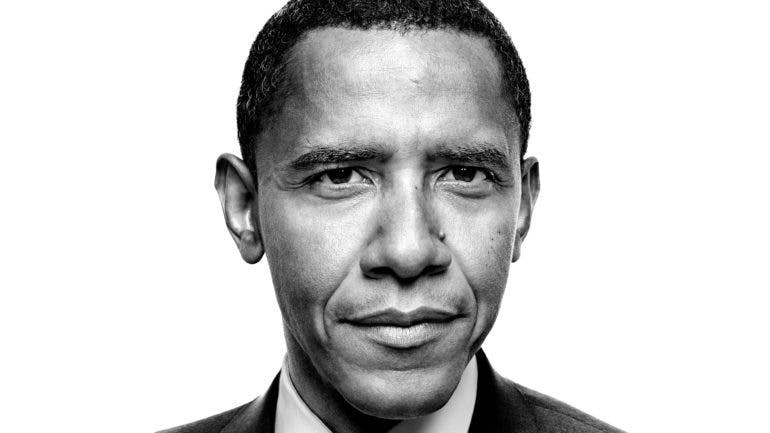

Platon on Photographing Politicians

From Barack Obama to Vladimir Putin, Platon has photographed many leaders on different ends of the political spectrum. Of course, he has his views. And although I refrained from asking where he stood on the political line, I did ask how he stopped differing political values from impacting his shoots. “…in order to do my job properly, I must not judge. I must connect,” he explains. “If I’m judging…it clouds my capacity to be observant. And as a photographer, we have to be really observant. We can’t go in with preconceived judgments because then you’re shutting down windows of opportunity to discover something new.”

Platon’s ability to photograph without judgment is evident in the images he makes. Powerful leaders are often depicted as larger-than-life characters. We remove them from normal society, placing them in a world unknown to the masses. Yet Platon’s methods, and certainly his images, humanize these people. The portraits he creates takes them off the pedestal society places them on. They remind us that at their core, they’re just like you and me: they’re human.

I asked Platon if he intended to show the world that his political subjects are in many ways similar to the rest of society. He explained to me how supremacy doesn’t exist. Meaning it in the sense that no one person is above the other, but rather we – the people – are told to believe they are. “So it just so happens that my pictures became more and more about trying to create authentic moments with people, rather than trying to perpetuate something that doesn’t really exist,” he explains.

At this point, he reflects on how he broke into photographing the political field. “JFK Jr started a magazine in the late nineties called George magazine…He [JFK Jr] wanted to show politics from the inside…we both wanted to humanize the system.”

During this time, Platon learned the importance of being authentic. Speaking with him, it’s clear he doesn’t desire to conform, nor does he wish to disrupt. Instead, he presents himself as who he truly is. He treats all his subjects with respect, and he treats them all as equals.

“…Whether I am with Putin or a president in the white house, or [if] I’m in the middle of nowhere doing a human rights story or civil rights story…if I really believe that this moment is important and I’m going to invest all my passions into trying to create a really important connection with this person and try to listen and learn from them, [to find out] who are they really? Then that moment might well resonate with millions of people because they all start to understand that human story.”

On Photographing Civil Rights

Aside from photographing the world’s most famous people, Platon has done a lot of work focusing on civil and human rights. His career has taken him to many corners of the world. He has witnessed some of the most heartbreaking stories and environments faced by other human beings within that time.

His work has focused on difficult topics like sexual violence in Congo, immigration issues, and human rights for people with disabilities in Russia.

Conversing with him, I’d describe Platon as an empath. I believe he genuinely connects to the pain felt by others. Learning this led me to ask how he dealt, mentally, with the burdens of what he’s seen.

“It’s a difficult one. I mean, I’ll be honest, you know, at the beginning, I’d always come back from these trips emotionally – I don’t know what the word is – but you could say devastated…”

He continues to explain that he must tap into the intellectual side of his brain in the moment of creating the work. He cannot allow the emotional side to take over. Instead, he must concentrate on telling the stories of those that matter. He must find ways to produce something powerful so that people engage with his subjects’ experiences.

Because of his dedication to the cause, he often finds that he will release his pent-up emotions once he removes himself from the environment he works in. “I find myself doing things like I’m watching a soap commercial, and I’ll burst into tears. You know, because [my] emotions have been pushed so far that, that [I’m] always on the edge.”

“I don’t know if that’s post-traumatic stress or what…It normally lasts for a month or two when I come back from one of these missions. But the thing is, no matter what I’ll go through, I get to leave and come back to a privileged life.”

“I might feel a bit, you know, beaten up for a while, but the people I left are still there, and they’re dealing with the struggle as part of their day to day existence.”

Staying true to his values, Platon puts the vulnerable before himself. He uses his pain as fuel to go back, continue telling their stories, and continue driving for change. He made a promise to his subjects that he will tell their stories with emotion and dignity. Delivering that promise comes before his own struggles born out of doing the work.

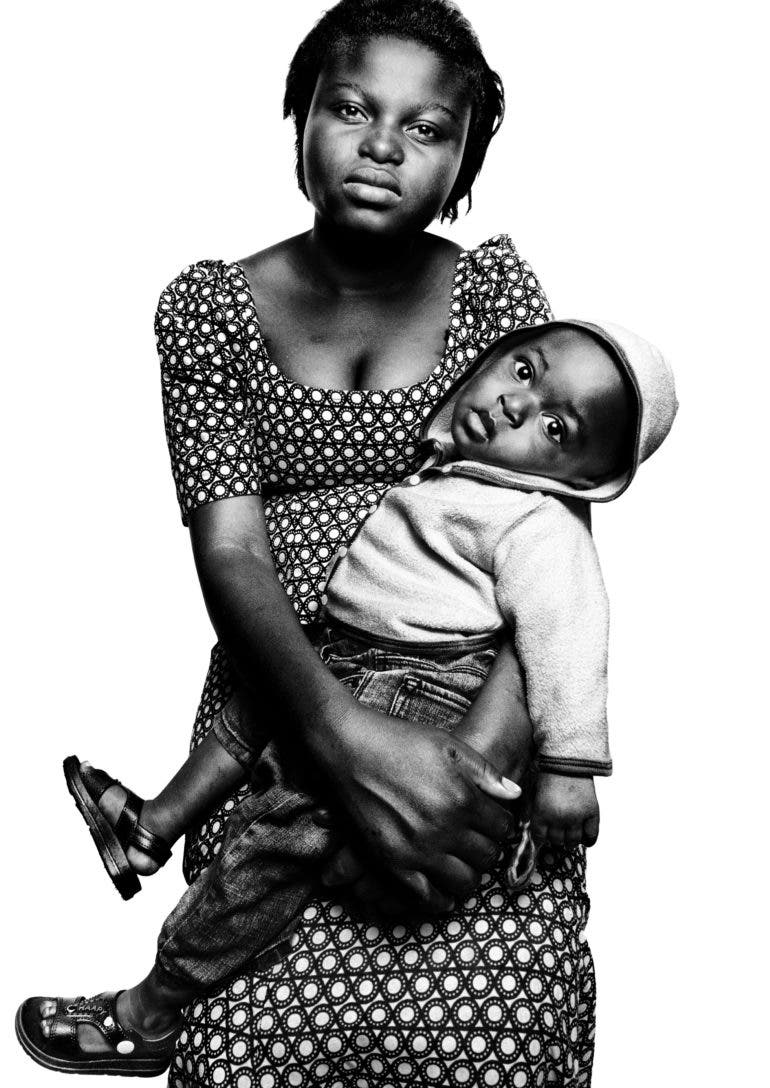

Meeting Esther

As we remain on the topic of human rights, the conversation turns to one of Platon’s more memorable subjects. Through the work of his foundation, The People’s Portfolio, he visited Congo. While there, he met a young woman called Esther. She had come to be photographed with her baby. Platon describes Esther as a “beautiful, loving person.”

Sadly, at the age of 16, Esther was kidnapped by a gang of criminals who ran a local mine. They kept her hostage for four days. During that time, the gang tied her to a tree and brutally raped her. Eventually, Esther was able to escape. Still wearing the wounds of her traumatic experience, she was able to get to the hospital. It was here that she was cared for by Dr Denis Mukwege, a man who treats women who have suffered sexual violence.

It wasn’t until Esther sat in front of Platon’s lens, a smile on her face, her son in her arms, that he learned the saddening truth: Esther’s son was born out of rape. “I burst into tears listening to this because you were asking me about my emotional state, and I’d never heard one woman tell me a story like this before,” he tells me. He continues, “…she’s telling me the story. I’ve got to take a picture here. I’ve got to function. So I picked up my camera, and she has this dignified, kind smile on her face.”

While making the portrait, Platon says to Esther, “I don’t know how you can [be] calm and smile to my camera. When you just told me the story that devastated me, I’ve never heard anything like that.” In response, Esther said, “The reason I’m not crying in your picture is because I don’t want to make you feel sad.”

It’s at this point in the interview that we both pause. While I can’t speak for Platon, I was taken back at the fact this brave young woman, who had suffered so much, could be so selfless. How the victim could become the comforter – it’s a testament to how strong Esther is.

On Not Making His Subjects Feel Like a Novelty

Unfortunately, many photographers from western society use suffering in the developing world as a catalyst for career progression. Prioritizing success over driving change, they use their subjects as an opportunity to make a name for themselves. Platon, in no way, matches that description. However, to his subjects, he could be another privileged photographer turning their pain into some novelty.

I asked how he creates a relationship that makes his subjects feel valued. “Trust is the biggest, most important factor in all my work. If I abused that trust, then I am a monster, and I have to live with myself.”

One of the most essential elements of building trust with his subjects, Platon explains, is telling the story on their terms. It’s not for him to put a political twist on their story. He’s not the author of their stories but rather the storyteller, sending their message to the rest of the world.

As he goes into further detail about how he approaches his missions, it becomes evident how much Platon wants to immerse himself in the local community. “I worked closely with the hospital, the doctors, and the nurses [in Congo]. The first thing I have to do is earn everyone’s trust.”

His approach is a far cry from the way parachute photojournalists operate. Instead of placing himself in an environment he knows little about, he becomes a part of the community, educating himself before considering making his first photograph.

“That’s why I worked with Dr Mukwege at the hospital,” he recalls. “All his staff became my teachers and my advisors. And I spent years building trust before I even photographed one of the victims or survivors of sexual violence.”

“So I felt that by the time I was actually there doing those pictures, I really had learned so much about how to approach this and try to be as dignified in my approach for these people, to allow them to be on their terms.”

On His Body of Work

In a career that has taken him all over the world, Platon has already achieved more than many ever will. His photographs will make even the most skilled photographer envious. So how does he feel about it all? His answer caught me off guard. “I hope it’s all practice for what I’m about to do…” he says. “I might be wrong, and it might be all over. Because you never know. But I would love to believe that it was all a big warmup…for the next thing.”

He then takes a short breath, taking the opportunity to have a brief moment of reflection. He continues, “…as [Mohammed] Ali once said to me, ‘you can shake up the world,’ but if I’m wrong, then that’s as good as I got…I’ll be very grateful for the ride I’ve had.”

Thinking back to his Netflix documentary, his opening comments, “I’m not really a photographer at all,” Again, I now understand. A skilled artist, yes. He’s put plenty of years into learning the craft. But Platon is an educator, a revolutionary, a voice for the voiceless, a father, a husband, and a wonderful man. As he says, “The camera is secondary to what I do.”