Pipeline attacker Darkside suddenly goes dark—here’s what we know

Darkside—the ransomware group that disrupted gasoline distribution across a wide swath of the US this week—has gone dark, leaving it unclear if the group is ceasing, suspending, or altering its operations or is simply orchestrating an exit scam.

On Thursday, all eight of the dark web sites Darkside used to communicate with the public went down, and they remain down as of publication time. Overnight, a post attributed to Darkside claimed, without providing any evidence, that the group’s website and content distribution infrastructure had been seized by law enforcement, along with the cryptocurrency it had received from victims.

The dog ate our funds

“At the moment, these servers cannot be accessed via SSH, and the hosting panels have been blocked,” the post stated, according to a translation of the Russian-language post published Friday by security firm Intel471. “The hosting support service doesn’t provide any information except ‘at the request of law enforcement authorities.’ In addition, a couple of hours after the seizure, funds from the payment server (belonging to us and our clients) were withdrawn to an unknown account.”

The post went on to claim that Darkside would distribute a decryptor free of charge to all victims who have yet to pay a ransom. So far, there are no reports of the group delivering on that promise.

If true, the seizures would represent a big coup for law enforcement. According to newly released figures from cryptocurrency tracking firm Chainalysis, Darkside netted at least $60 million in its first seven months, with $46 million of it coming in the first three months of this year.

Identifying a Tor hidden service would also be a huge score, since it likely would mean that either the group made a major configuration error in setting the service up or law enforcement knows of a serious vulnerability in the way the dark web works. (Intel471 analysts say that some of Darkside’s infrastructure is public-facing—meaning the regular Internet—so malware can connect to it.)

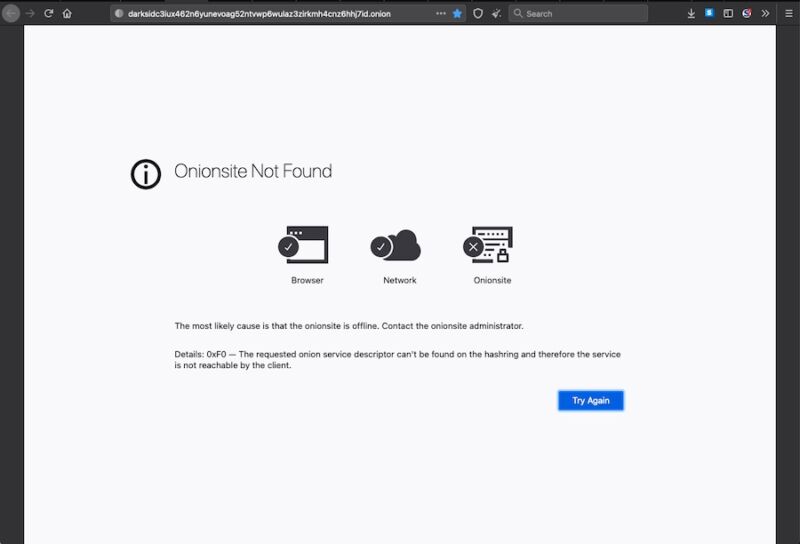

But so far, there’s no evidence to publicly corroborate these extraordinary claims. Typically, when law enforcement from the US and Western European countries seize a website, they post a notice on the site’s front page that discloses the seizure. Below is an example of what people saw after trying to visit the site for the Netwalker group after the site was taken down:

So far, none of the Darkside sites display such a notice. Instead, most of them time out or show blank screens.

What’s even more doubtful is the claim that the group’s considerable cryptocurrency holdings have been taken. People who are experienced in using digital currency know not to store it in “hot wallets,” which are digital vaults connected to the Internet. Because hot wallets contain the private keys needed to transfer funds to new accounts, they’re vulnerable to hacks and the types of seizures claimed in the post.

For law enforcement to confiscate the digital currency, Darkside operators likely would have had to store it in a hot wallet, and the currency exchange used by Darkside would have had to cooperate with the law enforcement agency or been hacked.

I very much doubt that a ransomware group keeps its profits in a hot wallet on a cryptocurrency exchange that would cooperate with the law enforcement. They go to shady exchanges only when they need to launder the money. Even then, blocking would be more believable than transfer.

— Vess (@VessOnSecurity) May 14, 2021

It’s also feasible that close tracking by an organization like Chainalysis identified wallets that received funds from Darkside, and law enforcement subsequently confiscated the holdings. Indeed, Elliptic, a separate blockchain analytics company, reported finding a Bitcoin wallet used by DarkSide to receive payments from its victims. On Thursday, Elliptic reported, it was emptied of $5 million.

At the moment, it’s not known if that transfer was initiated by the FBI or another law enforcement group, or by Darkside itself. Either way, Elliptic said the wallet—which since early March had received 57 payments from 21 different wallets—provided important clues for investigators to follow.

“What we find is that 18% of the Bitcoin was sent to a small group of exchanges,” Elliptic Co-founder and Chief Scientist Tom Robinson wrote. “This information will provide law enforcement with critical leads to identify the perpetrators of these attacks.”

Nonsense, hype, and noise

Darkside’s post came as a prominent criminal underground forum called XSS announced that it was banning all ransomware activities, a major about-face from the past. The site was previously a significant resource for the ransomware groups REvil, Babuk, Darkside, LockBit, and Nefilim to recruit affiliates, who use the malware to infect victims and in exchange share a cut of the revenue generated. A few hours later, all Darkside posts made to XSS had come down.

In a Friday morning post, security firm Flashpoint wrote:

According to the administrator of XSS, the decision is partially based on ideological differences between the forum and ransomware operators. Furthermore, the media attention from high-profile incidents has resulted in a “critical mass of nonsense, hype, and noise.” The XSS statement offers some reasons for its decision, particularly that ransomware collectives and their accompanying attacks are generating “too much PR” and heightening the geopolitical and law enforcement risks to a “hazard[ous] level.”

The admin of XSS also claimed that when “Peskov [the Press Secretary for the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin] is forced to make excuses in front of our overseas ‘friends’—this is a bit too much.” They hyperlinked an article on the Russian News website Kommersant entitled “Russia has nothing to do with hacking attacks on a pipeline in the United States” as the basis for these claims.

Within hours, two other underground forums—Exploit and Raid Forums—had also banned ransomware-related posts, according to images circulating on Twitter.

REvil, meanwhile, said it was banning the use of its software against health care, educational, and governmental organizations, The Record reported.

Ransomware at a crossroads

The moves by XSS and REvil pose a major short-term disruption of the ransomware ecosystem since they remove a key recruiting tool and source of revenue. Long-term effects are less clear.

“In the long run, it’s hard to believe the ransomware ecosystem will completely fade out, given that operators are financially motivated and the schemes employed have been effective,” Intel471 analysts said in an email. They said it was more likely that ransomware groups will “go private,” meaning they will no longer publicly recruit affiliates on public forums, or will unwind their current operations and rebrand under a new name.

Ransomware groups could also alter their current practice of encrypting data so it’s unusable by the victim while also downloading the data and threatening to make it public. This double-extortion method aims to increase the pressure on victims to pay. The Babuk ransomware group recently started phasing out its use of malware that encrypts data while maintaining its blog that names and shames victims and publishes their data.

“This approach allows the ransomware operators to reap the benefits of a blackmail extortion event without having to deal with the public fallout of disrupting the business continuity of a hospital or critical infrastructure,” the Intel471 analysts wrote in the email.

For now, the only evidence that Darkside’s infrastructure and cryptocurrency have been seized is the words of admitted criminals, hardly enough to consider confirmation.

“I could be wrong, but I suspect this is simply an exit scam,” Brett Callow, a threat analyst with security firm Emsisoft told Ars. “Darkside get to sail off into the sunset—or, more likely rebrand—without needing to share the ill-gotten gains with their partners in crime.”