Florida water plant compromise came hours after worker visited malicious site

An employee for the city of Oldsmar, Florida, visited a malicious website targeting water utilities just hours before someone broke into the computer system for the city’s water treatment plant and tried to poison drinking water, security firm Dragos said Tuesday. Ultimately, the site likely played no role in the intrusion, but the incident remains unsettling, the security firm said.

The website, which belonged to a Florida water utility contractor, had been compromised in late December by hackers who then hosted malicious code that seemed to target water utilities, particularly those in Florida, Dragos researcher Kent Backman wrote in a blog post. More than 1,000 end-user computers visited the site during the 58-day window that the site was infected.

One of those visits came on February 5 at 9:49 am ET from a computer on a network belonging to the City of Oldsmar. In the evening of the same day, an unknown actor gained unauthorized access to the computer interface used to adjust the chemicals that treat drinking water for the roughly 15,000 residents of the small city about 16 miles northwest of Tampa.

The intruder changed the level of lye to 11,100 parts per million, a potentially fatal increase from the normal amount of 100 ppm. The change was quickly detected and rolled back.

So-called watering-hole attacks have become frequent in computer hacking crimes that target specific industries or groups of users. Just as predators in nature lie in wait near watering holes used by their prey, hackers often compromise one or more websites frequented by the target group and plant malicious code tailored to those who visit them. Dragos said the site it found appeared to target water utilities, especially those in Florida.

“Those who interacted with the malicious code included computers from municipal water utility customers, state and local government agencies, various water industry-related private companies, and normal internet bot and website crawler traffic,” Backman wrote. “Over 1,000 end-user computers were profiled by the malicious code during that time, mostly from within the United States and the State of Florida.”

Here’s a map showing the locations of those computers:

Detailed information collected

The malicious code gathered more than 100 pieces of detailed information about visitors, including their operating system and CPU type, browser and supported languages, time zone, geolocation services, video codecs, screen dimensions, browser plugins, touch points, input methods, and whether cameras, accelerometers, or microphones were present.

The malicious code also directed visitors to two separate sites that collected cryptographic hashes that uniquely identified each connecting device and uploaded the fingerprints to a database hosted at bdatac.herokuapp[.]com. The fingerprinting script used code from four different code projects: core-js, UAParser, regeneratorRuntime, and a data-collection script observed on only two other websites, both of which are associated with a domain registration, hosting, and web development company.

Dragos said it found only one other site serving the complex and sophisticated code to visitors. The site, DarkTeam[.]store, purports to be an underground market that supplies thousands of customers with gift cards and accounts. A portion of the site, company researchers found, may also be a check-in location for systems infected with a recent variant of botnet malware known as Tofsee.

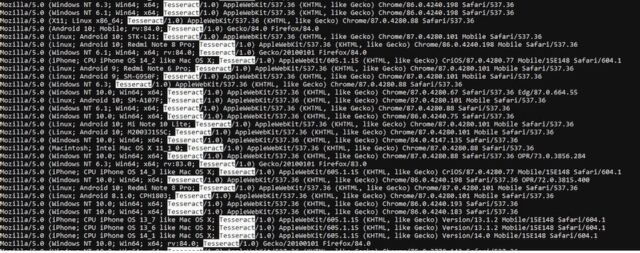

Dragos also uncovered evidence that the same actor hacked the DarkTeam site and the water-infrastructure construction company site on the same day, December 20, 2020. Dragos observed 12,735 IP addresses it suspects are Tofsee-infected systems connecting to a nonpublic page, meaning it required authentication. The browser then presented a user agent string with a peculiar “Tesseract/1.0” artifact in it.

Not your typical watering hole

“With the forensic information we collected so far, Dragos’ best assessment is that an actor deployed the watering hole on the water infrastructure construction company site to collect legitimate browser data for the purpose of improving the botnet malware’s ability to impersonate legitimate web browser activity,” Backman wrote. “The botnet’s use of at least ten different cipher handshakes or JA3 hashes, some of which mimic legitimate browsers, compared to the widely published hash of a single handshake of a previous Tofsee bot iteration, is evidence of botnet improvement.”

Dragos, which helps secure industrial control systems used by governments and private companies, said it initially worried that the site posed a significant threat because of its:

- Focus on Florida

- Temporal correlation to the Oldsmar intrusion

- Highly encoded and sophisticated JavaScript

- Few code locations on the Internet

- Similarity to watering-hole attacks by other ICS-targeting activity groups such as DYMALLOY, ALLANITE, and RASPITE.

Ultimately, Dragos doesn’t believe the watering-hole site served malware delivered any exploits or tried to gain unauthorized access to visiting computers. Plant employees, government officials later disclosed, used TeamViewer on an unsupported Windows 7 PC to remotely access SCADA systems that controlled the water treatment process. What’s more, the TeamViewer password was shared among employees.

Backman, however, went on to say that the discovery should nevertheless be a wake-up call. Olsdmar officials didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

“This is not a typical watering hole,” he wrote. “We have medium confidence it did not directly compromise any organization. But it does represent an exposure risk to the water industry and highlights the importance of controlling access to untrusted websites, especially for Operational Technology (OT) and Industrial Control System (ICS) environments.”