The NSA warns enterprises to beware of third-party DNS resolvers

DNS over HTTPS is a new protocol that protects domain-lookup traffic from eavesdropping and manipulation by malicious parties. Rather than an end-user device communicating with a DNS server over a plaintext channel—as DNS has done for more than three decades—DoH, as DNS over HTTPS is known, encrypts requests and responses using the same encryption websites rely on to send and receive HTTPS traffic.

Using DoH or a similar protocol known as DoT—short for DNS over TLS—is a no brainer in 2021, since DNS traffic can be every bit as sensitive as any other data sent over the Internet. On Thursday, however, the National Security Agency said in some cases Fortune 500 companies, large government agencies, and other enterprise users are better off not using it. The reason: the same encryption that thwarts malicious third parties can hamper engineers’ efforts to secure their networks.

“DoH provides the benefit of encrypted DNS transactions, but it can also bring issues to enterprises, including a false sense of security, bypassing of DNS monitoring and protections, concerns for internal network configurations and information, and exploitation of upstream DNS traffic,” NSA officials wrote in published recommendations. “In some cases, individual client applications may enable DoH using external resolvers, causing some of these issues automatically.”

DNS refresher

More about the potential pitfalls of DoH later. First, a quick refresher on how the DNS—short for domain name system—works.

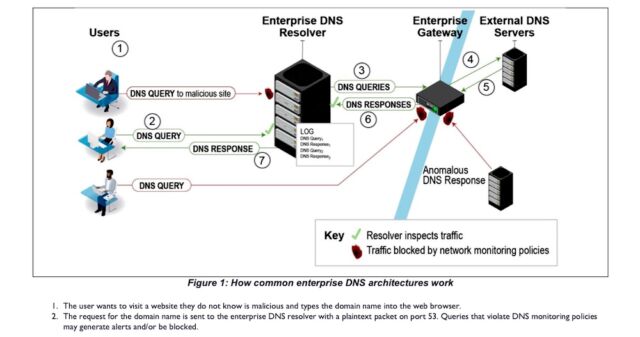

When people send emails, browse a website, or do just about anything else on the Internet, their devices need a way to translate a domain name into the numerical IP address servers use to locate other servers. For this, the devices send a domain lookup request to a DNS resolver, which is a server or group of servers that typically belong to the ISP, or enterprise organization the user is connected to.

If the DNS resolver already knows the IP address for the requested domain, it will immediately send it back to the end user. If not, the resolver forwards the request to an external DNS server and waits for a response. Once the DNS resolver has the answer, it sends the corresponding IP address to the client device.

The image below shows a setup that’s typical in many enterprise networks:

Astonishingly, this process is by default unencrypted. That means that anyone who happens to have the ability to monitor the connection between an organization’s end users and the DNS resolver—say, a malicious insider or a hacker who already has a toehold in the network—can build a comprehensive log of every site and IP address these people connect to. More worrying still, this malicious party might also be able to send users to malicious sites by replacing a domain’s correct IP address with a malicious one.

A double-edged sword

DoH and DoT were created to fix all of this. Just as transport layer security encryption authenticates Web traffic and hides it from prying eyes, DoH and DoT do the same thing for DNS traffic. For now, DoH and DoT are add-on protections that require extra work on the part of end users of the administrators who serve them.

The easiest way for people to get these protections now is to configure their operating system (for instance Windows 10 or macOS), browser (such as Firefox or Chrome), or another app that supports either DoH or DoT.

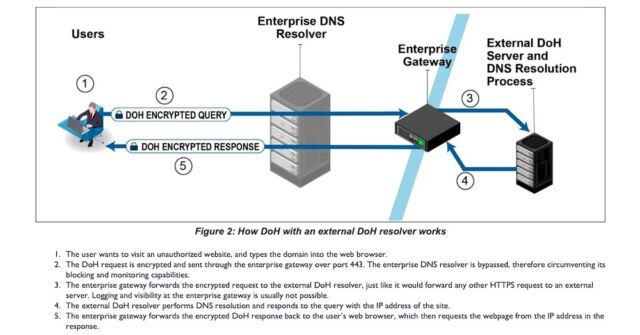

Thursday’s recommendations from the NSA warn that these types of setups can put enterprises at risk—particularly when the protection involves DoH. The reason: device-enabled DoH bypasses network defenses such as DNS inspection, which monitors domain lookups and IP address responses for signs of malicious activity. Instead of the traffic passing through the enterprise’s fortified DNS resolver, DoH configured on the end-user device bundles the packets in an encrypted envelope and sends it to an off-premises DoH resolver.

NSA officials wrote:

Many organizations use enterprise DNS resolvers or specific external DNS providers as a key element in the overall network security architecture. These protective DNS services may filter domains and IP addresses based on known malicious domains, restricted content categories, reputation information, typosquatting protections, advanced analysis, DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC) validation, or other reasons. When DoH is used with external DoH resolvers and the enterprise DNS service is bypassed, the organization’s devices can lose these important defenses. This also prevents local-level DNS caching and the performance improvements it can bring.

Malware can also leverage DoH to perform DNS lookups that bypass enterprise DNS resolvers and network monitoring tools, often for command and control or exfiltration purposes.

There are other risks as well. For instance, when an end-user device with DoH enabled tries to connect to a domain inside the enterprise network, it will first send a DNS query to the external DoH resolver. Even if the request eventually fails over to the enterprise DNS resolver, it can still divulge internal network information in the process. What’s more, funneling lookups for internal domains to an outside resolver can create network performance problems.

The image immediately below shows how DoH with an external resolver can completely bypass the enterprise DNS resolver and the many security defenses it may provide.

Bring your own DoH

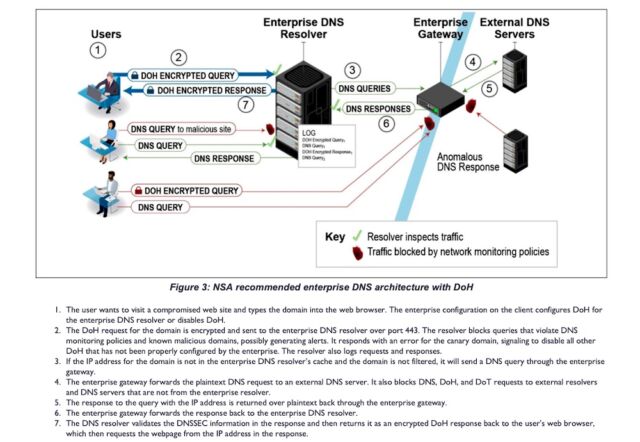

The answer, Thursday’s recommendations said, are for enterprises wanting DoH to rely on their own DoH-enabled resolvers, which besides decrypting the request and returning an answer also provide inspection, logging, and other protections.

The recommendations go on to say that enterprises should configure network security devices to block all known external DoH servers. Blocking outgoing DoT traffic is more straightforward, since it always travels on port 853, which enterprises can block wholesale. That option isn’t available for curbing outgoing DoH traffic because it uses port 443, which can’t be blocked.

The image below shows the recommended enterprise set up.

DoH from external resolvers are fine for people connecting from home or small offices, Thursday’s recommendations said. I’d go a step further and say that it’s nothing short of crazy for people to use unencrypted DNS in 2021, after all the revelations over the past decade.

For enterprises, things are more nuanced.