Man Ray: The Unwilling Fashion Photographer Who Excelled

Man Ray is today regarded as one of the most innovative photographers of the twentieth century. He reinvented solarization and further developed photograms, which he called “rayographs,” in reference to himself. He also pioneered fashion photography in the 1920s-1940 in Paris but did not want to be known as a “photographer.” He considered himself a painter and artist above all.

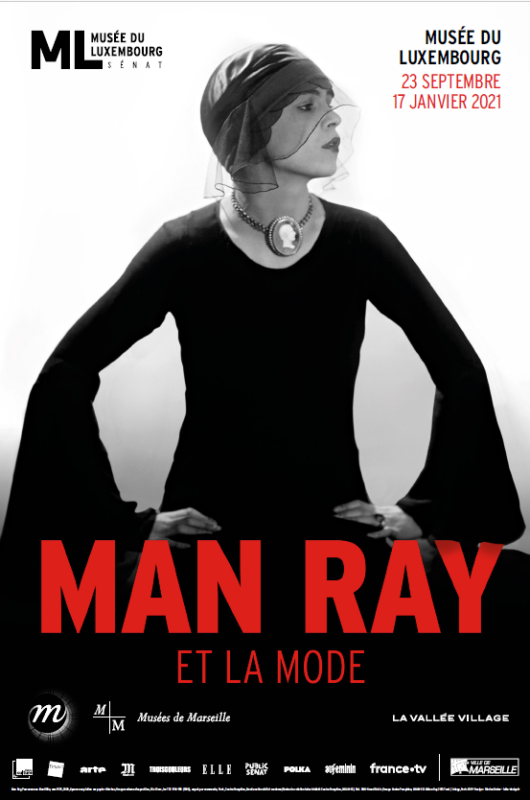

Man Ray and Fashion is an exhibition organized by the Réunion des Musées Nationaux – Grand Palais and the City of Marseille, at Musée du Luxembourg, Paris. Man Ray is presented here in a new light as his photography has never been explored from a fashion perspective.

Man Ray was a notable player in the artistic life in interwar Paris and of Surrealism in particular. Man Ray and Fashion is made up of the following sections: From 1920s Portraiture to Fashion Photography, The Rise of Fashion and Advertising, and the heyday of fashion photography: The Bazaar Years.

It displays more than 200 prints of the artist’s black-and-white images alongside magazines, haute couture, and film clips. It demonstrates how fashion influenced his work and how he influenced the fashion industry and almost created fashion photography.

Man Ray’s birth name was Emmanuel Radnitzky, and he was born in Philadelphia on August 27, 1890. His parents were Russian Jewish immigrants. After moving to the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, in 1912, the family changed their name to Ray in reaction to the ethnic discrimination prevalent at the time. Emmanuel was called “Manny,” and he started using Man Ray as his name.

Man Ray, who had studied drawing and draftsmanship in high school, initially bought a camera around 1915 merely to record his paintings, but he soon learned to use it artistically.

He moved to Paris in 1921, where his dream was to mix with Dada and Surrealist circles, but that did not go too well.

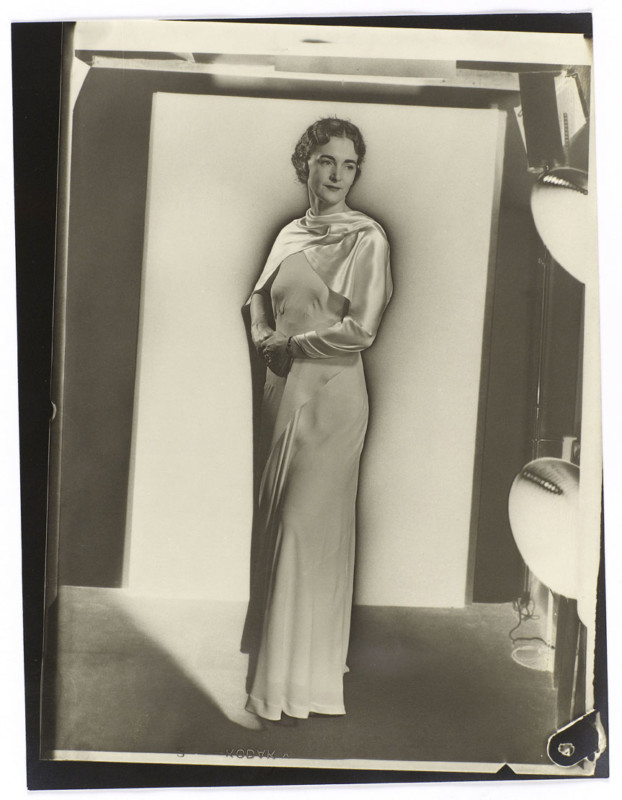

May Ray at first found work by focusing on society portraits to put food on the table. As he was looking for ways to make money quickly, he was introduced to fashion designer Paul Poiret by art critic Buffet-Picabia, wife of artist Francis Picabia. Poiret wanted the human element that painters lacked, and Man Ray found a niche for himself in photographing Poiret’s fashions.

Man Ray freely admitted to not knowing much about fashion photography and initially had difficulty lighting the model, but he was quick to learn on the job.

Fashion photography was not very popular in the early part of the last century as it was challenging to compete with illustrators who dominated the fashion press.

“Reproducing photographs was still very difficult and expensive at the time,” explains Catherine Örmen, co-curator of the Man Ray and Fashion exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg to the BBC.

Fashion photography was not easy a hundred years ago.

“For Man Ray, who worked before the development of ‘fast film’ and motor-drive cameras, there was no question of snapping pictures of models cavorting at hot spots or on the beach,” notes The New York Times in 1990. “The film was too slow; the model had to stand still.”

The models were not leaping off the page in vibrant poses, but the photographs showed excellent detail in the clothes, making the designers happy.

As Man Ray perfected his photography, word of his imagery’s high quality, which bordered on the experimental, began to spread. He started getting approached by most of the great couturiers, including Madeleine Vionnet, Coco Chanel, Augusta Bernard, Louise Boulanger, and above all, Elsa Schiaparelli.

Fashion magazines were attracted to his work, and he began working with Vanity Fair, French Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar.

Man Ray’s mother made clothes, and his father worked in a garment factory, which could also be connected to Man Ray’s interest in photographing fashion. Art historians have noted similarities between Ray’s collage and painting techniques and styles used for tailoring, as noted in Conversion to Modernism: The Early Work of Man Ray.

Kiki, Noire et Blanche (header photo above) was first published in French Vogue in May 1926. In this outstanding example of Surrealist art, Man Ray’s lover Kiki de Montparnasse poses with an African mask. The doubling of faces symbolizes divided subjects made up of the conscious and unconscious.

In the photo, as seen from left to right, it is white and black but the wordplay of the artist titled it “Noire et Blanche” or “Black and White”. If any of Man Ray’s imagery proves that he was more artist than a mere photographer, this is the supreme example.

Lee Miller his assistant would often take over Ray’s fashion assignments to enable him to concentrate on his painting. So closely did they collaborate that photographs taken by Miller during this period are credited to Ray.

Ray embraced all aspects of expressionistic art that flourished between World War I and II. Fashion photography was just a necessity for making a living.

As an artist who worked in several genres – painting, film, sculpture, printmaking, and the essay – he did not like the designation “photographer.” The pictures he took of women in Paris haute couture were to pay for his studio, his brushes, and his paint, he said.

During his time, one of the major art movements was Dadaism, which believed that the ordinary could become extraordinary through art and his reinvent of photograms dovetailed neatly into that thinking. Photograms are created by placing objects directly onto photographic paper and then exposing them to light.

Man Ray reinvented this technique and called it “rayographs.” He even moved the object during exposure to give it more depth and tonal range. This kind of imagery probably gave him more satisfaction as an artist than fashion photography, which was essentially putting bread on the table. Vanity Fair printed four of his rayographs in a feature.

“He later characterized his discovery as an unconscious, ‘automatic’ darkroom happening that occurred in his tiny bathroom/darkroom when he placed a small glass funnel, the graduate, and the thermometer in the tray on the wetted paper and turned on the light,” writes Robert Hirsch in his book Seizing the Light: A History of Photography.

It is essential to keep in mind that Man Ray was a painter, and he had done similar techniques in painting when he had put an object on the canvas and painted around it.

Man Ray also reinvented solarization (see sidenote below & Portrait of Unidentified Woman, above) and started using it in his fashion photography to make them look painterly.

He started working with Harper’s Bazaar in 1934, and it was this fashion magazine that bestowed Man Ray’s image as a fashion photographer. Art director Alexey Brodovitch wanted to innovate the magazine’s layout, and Man Ray’s creations were a perfect technical match for his visualizations.

Man Ray’s strange compositions, plays of light and shadow, solarizations, colorizations, and other technical experiments sprouted, dreamlike images that would create magazine pages that were not seen before.

Bradovitch granted Man Ray total creative freedom and “allowed him to produce images bordering on abstraction which embodied the very essence of fashion,” says Catherine Örmen, a co-curator of the Man Ray and Fashion exhibit.

Paris got engulfed in the Second World War as the German Wehrmacht began its entry into France in 1940, and it was then that Man Ray fled to the USA and Hollywood. Man Ray never enjoyed commercial photography and was now even more concerned that he would be viewed as just another commercial photographer and not an artist.

With all this in mind, he decided to abandon fashion photography, even though this would have been very lucrative in Hollywood given his reputation and experience in the fashion capital of the world. He resided in Los Angeles from 1940 to 1951 and during that time concentrated on painting rather than photography.

It is said that while in the US, he would often track down old magazines to look for his photos only to find them torn out. This would give him immense pleasure that readers were excited by his imagery and collecting it.

While in Paris, he had almost tried to conceal his professional photographer’s trade, even then preferring to position himself as a painter. He kept the prints he made to a minimum, printing only the contact sheet, and then just the images chosen for the publication. At that time, magazines owned the negatives in addition to the prints.

Man Ray always wanted to return to Paris, and he finally did so in 1951. There he continued his creative practice across different mediums. He even recreated earlier work in new forms. He died in Paris in 1976 from a lung infection.

Over the course of his career, Man Ray elevated the craft of fashion photography to an art form. He inspired photographers like Sarah Moon, Guy Bourdin, Paolo Roversi, and many more. Bourdin was turned away from Man Ray’s door six times by his wife and, on the seventh, finally succeeding in gaining the artist’s company when Man Ray himself answered the door and invited Bourdin in.

So, was Man Ray a fashion photographer or even a photographer? Sure, but it would be more accurate, and even autobiographical, to say that “Man Ray was a reluctant photographer.”

Sidenote: Did Man Ray or his assistant/lover re-discover (read popularize) the technique of solarization?

I guess they both did jointly over a darkroom accident. The story is that Lee Miller*, his assistant thought she felt a mouse running over her foot while she was working in the darkroom in Paris, and promptly turned on the light (after screaming her lungs out!), exposing the photograph that was in the developer. Imagine Man Ray’s surprise when he saw that the photo had turned part negative and part positive to create a surrealistic image.

Although solarization was known to the early pioneers, including Daguerre, John William Draper, and J.W.F. Herschel, Man Ray helped popularize it by using it in his fashion photography published in major magazines.

* Miller was accredited with the U.S. Army as a war photographer for Condé Nast Publications during World War II. Miller was famously photographed by LIFE photographer David E. Scherman taking a bath in Hitler’s Munich apartment.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him via email here.

Image credits: Header photos “Kiki, Noire et Blanche” by Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons