Badrish Isdin Freezes the Movement of Musicians in Time

For more stories like this, subscribe to The Phoblographer.

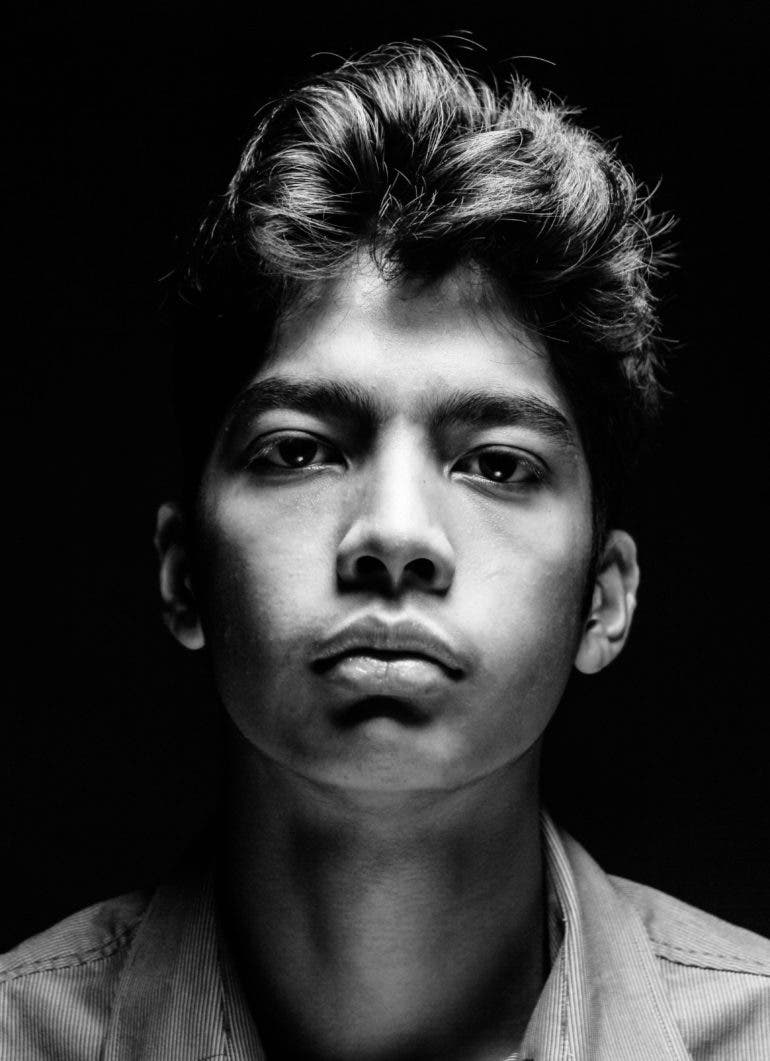

“Life can move quickly sometimes, passing by in a blur, and I enjoy the possibility of freezing a moment and capturing the impossible.”, says 20-year-old Badrish Isdin. As a musician and storyteller, he’s been using simple photography gear and capturing some striking portraits of musicians in motion.

Using flashes and strobes can be daunting for those who are new to photography. Add in a light modifier along with the factor of balancing ambient light in your exposure, and even experienced photographers like me can stutter. For this series of capturing what musicians look like during their sessions, Badrish gleaned inspiration from Harold Edgerton.

Affectionately known as Papa Flash, Edgerton was one of the first to use flashing lights to freeze motion that was too fast for the naked eye. In an era when flash photography meant using flash powder to create light out of a chemical reaction, he invented a type of light bulb he called a stroboscope. This bulb containing an inert gas could produce a flash of light for as short a duration as 10 microseconds (1/100,000th of a second). This allowed photographers to capture fast-moving subjects on the slow film stock available back then. With just one speedlight, a 50mm lens and a 1st generation DSLR, Badrish shows us that producing quality images with strobes doesn’t have to be complicated or confusing.

The Phoblographer: Tell us a bit about yourself and how you got into photography.

Badrish Isdin: I’m a 20 year old filmmaker and photographer who also dabbles in a lot of other creative outputs in the artistic world. My interest in photography came out of nowhere really, I’ve always been a film buff/cinephile and was always interested in telling stories. Although at a young age creating a whole film would not be as easy as taking a singular photograph. So I started taking pictures of things that caught my eye with the firm goal of telling a story. That helped me a lot with my creative development over the years as I would always have the mindset of creating an image that speaks volume and carries a narrative that could be interpreted in different ways by many.

The Phoblographer: What was the inspiration behind doing a stroboscopic project? Please elaborate on this.

Badrish Isdin: It all started as a small final year project for my A-Levels. I wanted to do something out of my comfort zone, something I’ve never done before as my other works before this focused on a more cinematic style of photography; similar to the style of Gregory Crewdson for example. So I did some research on studio photography that was more than just your every day “three point lighting” portrait and stumbled upon the works of Gjon Milli and his stroboscopic work. I was in awe and really wanted to give it a go and see what I could create. At the end of the day, the spirit of photography is in the capturing of a moment. Life can move quickly sometimes, passing by in a blur, and I enjoy the possibility of freezing a moment and capturing the impossible. He inspired me by being able to make the invisible, visible.

The Phoblographer: Why stroboscopic and not long exposure?

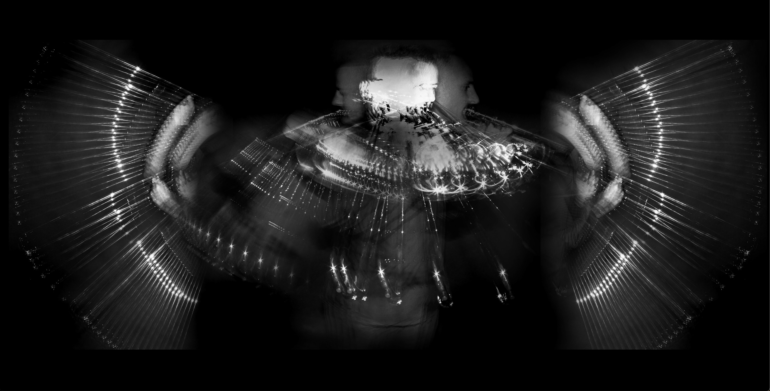

Badrish Isdin: To be fair, I’ve always been a sucker for what’s known as the “unseen world” in terms of paranormal and philosophical beliefs, therefore being able to capture the unseen movements of a human being in action, doing what they love, seeing every singular motion that goes into their craft (Almost soul-like) couldn’t have been achieved the way I wanted it to look if I were to solely create and shoot using long exposure techniques, even though it does play a part in terms of a very slow shutter speed that was used. So in some ways, it is an extension of long exposure photography with additional steps.

The Phoblographer: Your Behance page says that you would work on the ’theme of fragments’. What significance does this phrase hold towards the series?

Badrish Isdin: If I’m being honest, that was just a theme that was given to me by the examination board for my studies. Although artistically, this could have been shown in so many different ways, I specifically chose stroboscopic photography to create a narrative about the specific fragments in movement that we don’t see with the naked eye, which are crucial to a musician creating the sound they desire for an audience. This allows my audience to visualise a pandemonium of sound even without even hearing anything.

The Phoblographer: This could have been done with almost any moving subject inside a studio. What is it that led you to choose music as the theme for the project?

Badrish Isdin: It really was a super simple decision to go down this path. As I said before, I dabble in a lot of other aspects of the creative arts, and music is definitely another love of mine. Myself as a musician wanted to merge my two worlds and create something I can look at and constantly be proud and astonished by every time. Although the final image does follow the movements of a dancer. The reason I chose to end the series with a dancer instead of another instrumentalist was to create a sort of final product in the narrative of the series. As the music is set, the dancer creates a sense of closure, dancing to the tune composed by the musicians we see at the start.

The Phoblographer: Who were the subjects in the images, and what criteria did you base their selection on?

Badrish Isdin: They were friends really. The only criteria I had was a sense of passion in what they do. I didn’t just want to capture movement; I wanted to capture the feel, spirit and gusto of a musician in their element, as that is what music is about.

The Phoblographer: Tell us about the gear used for this series and why you chose it over anything else.

Badrish Isdin: I didn’t actually have access to expensive/high tech gear while doing this project as it was a project done for an exam. All I had was a studio, a Canon 5D, a 50mm prime lens, two external flashes (I only had to use one at the end of the day), and that’s it. Anyone is able to do this with the right understanding of the camera (basics are super important) and just diving a bit deeper into how to use an external flash for a different, more interesting purpose. I’ll give you a simple walkthrough for the flash, as the most confusing aspect of this shoot is setting up the flash. This is basically a “how to set your flash for stroboscopic photography for dummies”: On the flash (I used a 580 EXII), you need to hold down the “Mode” button, then you’ll see the letter “M ” start to blink. Hit the Mode button one more time, and the screen will read “Multi”, and a few new options will appear. This is [the] stroboscopic mode. The settings can be a bit confusing; there’s a set of numbers that appear (from left to right) to be a fraction, another random number, and a Hz setting. The “fraction” (such as 1/32) is the flash power. This setting is important because it controls the actual brightness of the flash. You are taking a photograph using multiple quick bursts of light, so it would be very easy to overexpose whatever you are attempting to shoot. So the flash power setting is very useful for controlling exposure. It would also be very easy to overwhelm your flash as well as your batteries if you were to shoot at full power. Going left to right, the next number is actually how many TOTAL flashes you’d like the flash to fire, so pick according to the subject you are shooting. The last number (shown in Hz) is how many times per second the flash will fire.

The Phoblographer: That looks like one high-speed strobe you’ve used. What calculations were done to decide the exposure time and the number of times to fire the strobe?

Badrish Isdin: For the shutter speed, you need to do some very simple math. The goal is to have the shutter open for as many flashes as you have the speedlite set for. In my example, I’m doing 10 flashes total, with the key being that there are five flashes per second. Just divide the total number of flashes by the flashes per second. So, in this case, the shutter speed should be 2 seconds (five flashes the first second, five flashes the 2nd second). I kept the aperture quite low, having a range from f5.6 – 8 and the ISO at 200 at all times.

The Phoblographer: What inspired your choice for doing this in black and white instead of color?

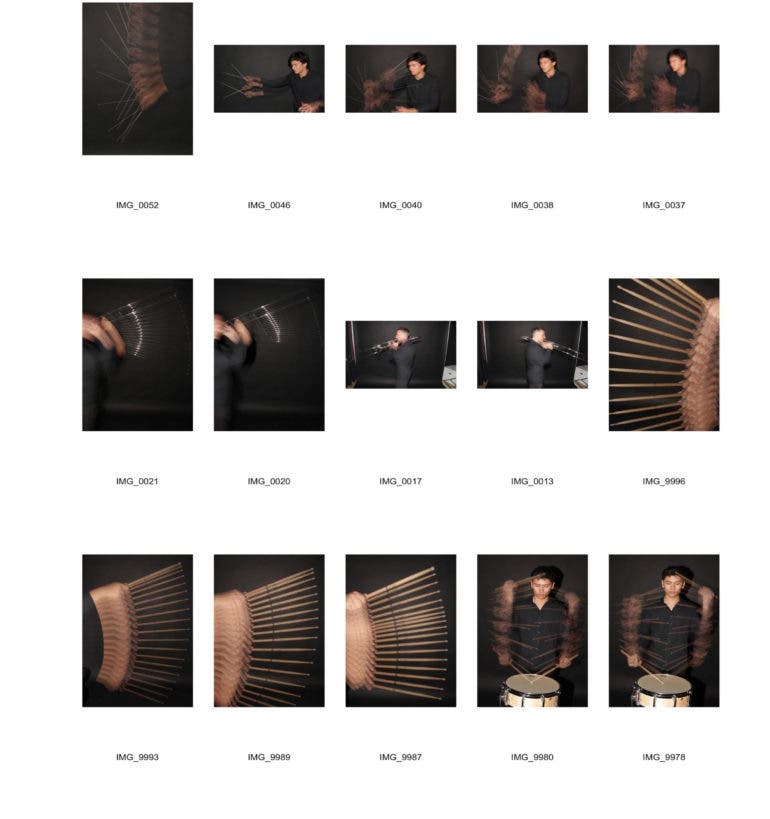

Badrish Isdin: I chose to make it black and white because it allowed the details of the movement to pop more and be seen a lot clearer. You can see from this contact sheet below that it is quite light and exposed, which is not really impactful to me. On the other hand, I did want to pay homage to Gjon [Mili]’s work, and he produced most of his stroboscopic work in black and white

The Phoblographer: I like how the background is lost in the darkness.

Badrish Isdin: It was simply a black background which was not lit in any way. Although I did have to go through post-processing to really darken it, allowing the main subject to come forward a lot more and creating that dark abyss to contrast the chaos happening in the foreground

The Phoblographer: The first image you took on the day was probably the trial run for the rest. Were there many retakes required to get each shot in the series?

Badrish Isdin: It was! It took a lot of figuring out to get right in the first place, mainly because I was a teenager when I did this, who didn’t really want to read and research on things as it looked boring. I would rather try figuring it out in the studio itself; trial and error is the best way to learn. But in the end, I had to do my homework and really understand the mechanics [of] how to do it right. Besides it being a test run, it was also a recreation of Milli’s piece with drummer Gene Krupa. Before I would go do my own thing, I decided to honour the man himself and see if I could create as close as possible what he made. It truly is mindblowing to know he did that without the technology we have today.

The Phoblographer: Would you say there was a significant amount of post-processing required to achieve the final look? Take us through the editing workflow for one of the images.

Badrish Isdin: So to edit, I used both Lightroom and Photoshop. Lightroom specifically to adjust the levels, contrast, exposure etc, and on Photoshop, it was a lot of overlaying and stitching images together. Some of the shots came out quite dim and light, while I wanted it to be heavier and more intricate in detail. So I decided to layer shots and create a more chaotic image than what I have originally. And of course, in terms of stitching, there is the composition with the main subject movement in the middle and a mirrored image on both sides of a different angle of the musician.

Workflow wise, let’s take the drummer, for example. I would take all three images of him and convert it to black and white as I shot in colour. [The] main thing is to adjust the levels, curves and contrast as similar to each other as possible to make the stitch at the end seamless. I would clean up any parts I think creates a distraction in the image and load it into photoshop. Stitching it together would be an easy process as the image should blend seamlessly due to the post-processing done to it. I would move things around and overlay images based on my liking and what I think is the most interesting way of portraying the image, and I’m basically done. A touch up happens here and there if needed.

The Phoblographer: In addition to the different way this series shows how musicians move, was there a story you wanted to convey?

Badrish Isdin: Well, as I said at the start, everything I create stems from me wanting to tell a story. In this case, I wanted to tell the story of the musicians. The movement they make to create the sound we enjoy listening to is what we don’t see when they perform both figuratively and literally. The amount of strokes they take in hours and hours of practice to perfect their artistry behind the scenes is something we don’t see but hear in their end product, but this time it is somewhat visualise[d] for you to see.

All images by Badrish Isdin. Used with permission. Visit his Behance page for more.