Will Burrard-Lucas Went on a Quest to Find a Rare Black Leopard in Africa

For more stories like this, please subscribe to The Phoblographer.

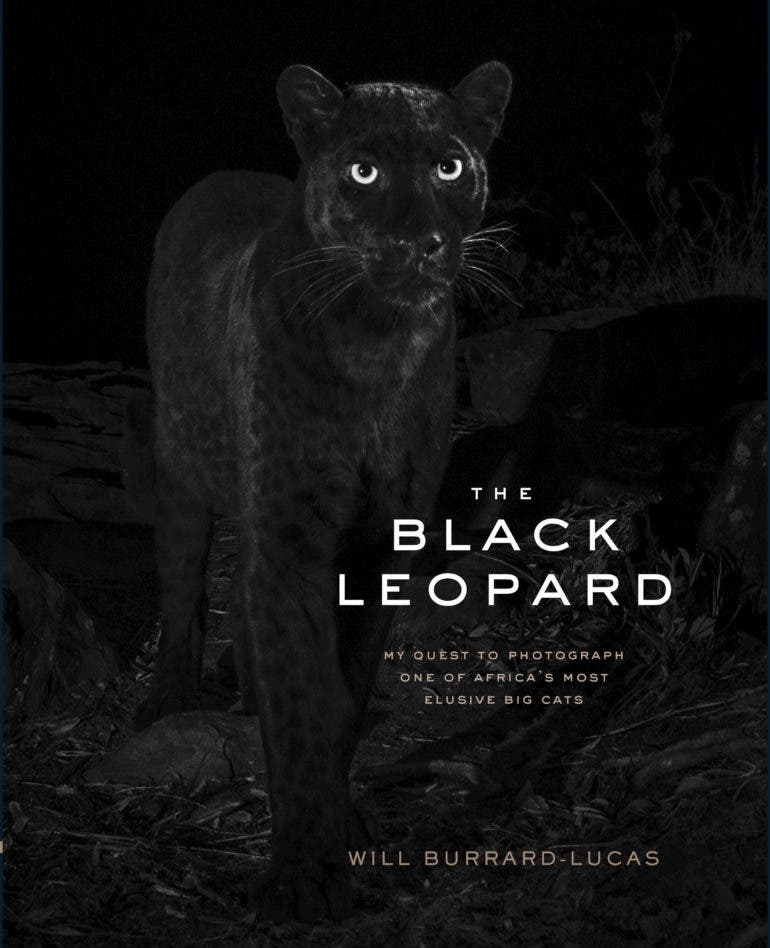

“At night, it was always the black leopard’s eyes that struck me,” Will Burrard-Lucas remembers. “In fact, he was usually completely invisible in the black of night, except for his eyes reflecting brightly in my torch beam.” The wildlife photographer saw his first spotty leopard in Tanzania at the tender age of five. Just over thirty years later, he stood face-to-face with a rare black leopard in Laikipia, Kenya. With the thrum of crickets and the occasional call of a rock hyrax filling the air, their eyes met for just an instant before the panther slinked away in the dark.

Want to have your work featured? Click here to see the many ways to submit.

Black leopards have melanism, the opposite of albinism, resulting in their inky coats. No one knows how many of them there are in Africa: these animals are famously elusive. And in Africa, they’re less likely than their spotty siblings to survive into adulthood. But if you’re lucky, you might hear whispers of one living in the wild. Burrard-Lucas’s encounter with such a leopard, whom he nicknamed “Blacky,” is one he had dreamed of for as long as he could remember.

Since then, he’s seen the same leopard in person a total of six times. In just over a year, he would create twenty-six stunning photos of the animal using a camera trap system of his own creation. In that time, he saw the shy animal grow from a youngster to an adult. Now, the photographer’s decades-long quest for the black leopard, culminating in Laikipia, is chronicled in the extraordinary photo book and memoir, The Black Leopard, published by Chronicle Books. We asked him more about his time searching for this once-in-a-lifetime subject.

The Essential Photography Gear of Will Burrard-Lucas:

Burrard-Lucas tells us:

“When I started this project, I knew my chances of catching a glimpse of this elusive cat were very slim, let alone photographing it in the traditional sense. I knew that this would only be possible with camera traps–cameras that are left out for a long period of time with a sensor that detects a passing animal and automatically photographs it. By setting up many cameras all over the leopard’s territory and leaving them for long enough, I hoped I would be successful.

“In 2012, I started developing my own camera trap system, which I have since used to photograph rare and nocturnal creatures across Africa and also made available to other photographers and filmmakers through my company, Camtraptions. It was five of my Camtraptions camera traps that I first deployed in Laikipia in early 2019 and which I used to take all of the black leopard photographs in the book.

“The set-up consists of a sensor to detect the animal, a DSLR camera in a housing, and flashes triggered using wireless triggers. I would often leave a set-up running for a month or more before returning to download images and change batteries.

“I only ever managed to photograph the black leopard at night, I suppose because he usually lies low during the day when he is more easily spotted by prey. Camera traps are ideally suited to photographing wildlife at night because they allow complex lighting to be set up in advance. It can sometimes take many hours to perfect the composition, visualizing where the animal will be when it triggers the camera and how the lighting will fall across the scene.

“For several years now, I have focussed on photographing wildlife at night, as the low-light sensitivity of modern cameras has opened up this new frontier in wildlife photography. It is now possible to photograph an animal and stars in the night sky in a single exposure by combining a long exposure time with flash and a high sensitivity setting. It was my ultimate ambition to capture such an image showing the black leopard under a star-filled night sky. As I chronicle in this blog post, after many months of perseverance, I eventually managed to get the shot.“

Phoblographer: You found the black leopard after connecting with the local wildlife community at Laikipia Wilderness Camp in Kenya. What did you learn from the team there?

Will Burrard-Lucas: I already knew quite a bit about leopards from my time in South Luangwa, which is one of the best places in Africa to see leopards in the wild. Mostly, I needed to learn about the unfamiliar habitat in Laikipia and how the leopards were using the land. The guides, researchers, and rangers showed me water sources, tracks, and trees that they believed the leopards favored. This was essential information in the early stages of the project, which helped inform my placement of cameras.

Phoblographer: Can you tell us about Blacky, the individual you encountered in Kenya, and his history as far as you know it?

Will Burrard-Lucas: At the time I first arrived in Laikipia, the black leopard was approximately two years old. He had first been spotted about 18 months earlier by the landowner, Luisa, and the chief ranger, Mohammad. When they first saw him, he was a small cub, and they only realized he was a leopard when they realized he was following a spotty leopard (the mother). They had never seen a black leopard before, even though they had occasionally been reported in Laikipia.

Thereafter, Luisa and her team saw him every now and then. The guides from Laikipia Wilderness also spotted him a handful of times near Luisa’s boundary. It was via the guides at Laikipia Wilderness camp that I first heard about the leopard. When I first photographed him, he was no longer staying by his mother’s side but he was still sharing her territory. As my project progressed, he was gradually pushed away by a big spotty male. As far as I know, he still has not established a firm territory of his own.

Phoblographer: Readers should get the book to learn all of the incredible story, but can you tell us about just one of your face-to-face encounters with Blacky?

Will Burrard-Lucas: I saw him a few times but just once during daylight, when I got a call from Mohammed to say he had seen the leopard down in the valley. I grabbed my camera and rushed to look for him. I soon found him, as he really stood out against the vegetation. I was too far away to capture good images, but I was able to capture this video footage.

Phoblographer: Were you ever frightened of Blacky?

Will Burrard-Lucas: I was never frightened. He was always more nervous of me than I was of him. If I ever surprised him, he would just run away. A leopard is only likely to be dangerous if cornered or perhaps a mother protecting her cub. There was a much greater risk from snakes lurking in the rocks or from surprising an elephant or old buffalo in a thicket.

Phoblographer: What are some of the conservation challenges facing leopards like Blacky in Laikipia County, and what can be done to help them?

Will Burrard-Lucas: The main threat to predators in Laikipia comes from human-wildlife conflict, particularly near villages where leopards, hyenas, and lions may occasionally kill livestock. This may lead to retaliatory poisoning of the predators. Supporting local communities can help mitigate the conflict, for example, by building predator-proof bomas to keep the livestock safe at night. Tourism can also bring revenue into local communities, which helps mitigate some of the challenges they face from living in close proximity to wildlife. San Diego Zoo is doing great work to conserve leopards in Laikipia.

Phoblographer: What ethical rules do you follow when documenting wildlife, and were there any additional rules you followed that are specific to leopards in Laikipia?

Will Burrard-Lucas: For me, the golden rule is to not do anything that could harm the subject. As photographers, we aren’t always qualified to know whether our actions might break this rule, so whenever trying anything new, I will partner with experts such as scientists, conservationists, or guides who know the species intimately and can help ensure the techniques I employ are responsible.

Devices such as BeetleCams and camera traps are just tools, and it is always up to the photographer to ensure they are used responsibly. Any tool can be used irresponsibly; be it a Land Rover getting too close to a cheetah with a kill, a microlight buzzing elephants as they cross a river, or a hide placed too close to a nest. Therefore, every tool needs to be evaluated carefully in the context of the environment and species in question, and it is then up to the photographer to act responsibly.

With camera traps, I always use the minimum flash power and use a high ISO (sensitivity) setting. I also avoid taking multiple images in quick succession (i.e. strobing). The resulting flash is therefore similar to a flash of lightning and does not blind the subject. For very sensitive subjects, I will often take the additional precaution of using infrared cameras with invisible infrared flashes. The very first image I captured of the black leopard was in infrared, but I soon found he wasn’t bothered by the camera so I switched to color.

Phoblographer: What were some of the practical and technical challenges that came with photographing the black leopard, especially at night?

Will Burrard-Lucas: Some animals, like the black leopard, may be very shy or rare. Catching a glimpse of them, let alone photographing them, can be a tremendous challenge. Camera traps are deployed for many weeks or months and automatically trigger when an animal passes by. Overcoming the technical difficulties of setting up these devices and capturing images with aesthetically pleasing composition and lighting is half the challenge.

The other half is knowing where to put the cameras. On my own, I would stand little chance of finding suitable spots, but by partnering with guides, conservationists, and researchers who have dedicated their lives to studying and protecting wildlife, my chances are greatly improved.

Lighting an animal that reflects almost no light at all, in the black of night, was also a great challenge. I found I had to expose two stops brighter than for a regular spotty leopard just to be able to see his body in the image. Achieving this without blowing out the rocks and vegetation meant I had to use snoots to shape the light.

Phoblographer: It was painful for you to say goodbye to Blacky. Do you plan to return to visit Laikipia in the future?

Will Burrard-Lucas: Yes. Over the course of the project, we made many good friends in Laikipia and we will certainly visit them in the future. On these trips, I will doubtless attempt to photograph the black leopard again, but I have no idea if he will still be around. I do occasionally hear of sightings, but it seems he is ranging far these days, so I don’t know where he will settle. He seems to be doing well and looks healthy.

Phoblographer: In what ways has this project reaffirmed your lifelong passion for photography?

Will Burrard-Lucas: Through wildlife photography, I have found a way to spend prolonged periods of time in the wild places where I am most at home, in the parts of the world where I can experience solitude and adventure and witness incredible natural beauty. Laikipia is a very special part of Kenya, and I certainly fell in love with the place and forged some great friendships.

I am now looking forward to working on new projects in new places and the adventures that my photography will bring me. I am also looking forward to finding new ways that I can use my photography to aid conservation efforts in these places that I love. Photography has the power to move people, and for that reason, I believe I will never lose my passion for it.

Phoblographer: You dedicated this book to your children, Primrose and Benjamin, who also encountered Blacky during your time working on this book. Do they talk about him often?

Will Burrard-Lucas: Having children suddenly made it much harder for me to leave home and be apart from my family. My wife and I, therefore, decided that whenever possible they would join me in the field. Traveling with young kids certainly presents challenges–not all accommodation is child-friendly, for example–but for us, it is a small price to pay.

Sharing my experiences with them is wonderful and helps me see the world through new eyes. I was thrilled that they got to see the black leopard. My daughter was four at the time, and she certainly still talks about it. Even if they can’t picture it, they will always be able to look at my photos and know that they were there.

All photos from The Black Leopard: My Quest to Photograph One of Africa’s Most Elusive Big Cats by Will Burrard-Lucas, published by Chronicle Books 2021. All images © Will Burrard-Lucas, courtesy the artist and Chronicle Books. Learn more about Will Burrard-Lucas by visiting his website. You can grab your copy of The Black Leopard: My Quest to Photograph One of Africa’s Most Elusive Big Cats via Chronicle Books or order a signed copy through the artist’s website. Follow Burrard-Lucas on Instagram at @willbl and on Facebook at @BLphotography.