Gøneja Captures the Magic of His Queer Community

For more stories like this, subscribe to The Phoblographer.

“My queer family are the first people I ever photographed,” the Berlin-based artist Gøneja tells me. “And they’re the ones I continue to portray to this day.” He’s embarked on countless adventures with this chosen family, whether they’re dancing the night away at Berghain, the iconic (and famously hard-to-get-into) club in the heart of the city, or spending the day exploring a quiet village in the Polish countryside. Their faces appear time and again, in darkened interiors and sun-drenched landscapes, as you make your way through his newest book, Rituals.

Want to get your work featured? Here’s how to do it!

“The people you see through the pages of the book are somehow all seekers and believers,” Gøneja says. “It is this spiritual quest, or perhaps a search for something bigger, that somehow runs as a thread throughout this work and weaves all the subjects together.” In their pictures, you’ll find echoes of Norse mythology, Sufism, and other centuries-old spiritual systems, set against the backdrop of the modern world. The portraits themselves are interspersed with evocative, empty landscapes captured throughout Europe, including a Neolithic monument in Scotland and a land art installation in Sicily.

Rituals is one photographer’s ode to the people he knows, the places he’s visited, and the gleaming, mystical moments that too often go unnoticed in the hustle and bustle of contemporary urban life. One of the photographs in the book, a portrait of Lea Rose, was recently recognized as a runner-up in the All Out Photo Awards, an international celebration of resistance, support, and healing in the LGBTQ+ community. We asked Gøneja more about the project. You can grab your copy of Rituals here.

The Essential Gear of Gøneja

Gøneja tells us:

“I never owned more than two cameras. For this series, they were: the Zenza Bronica ERTSi 645, an analog and medium-format one, and a Canon EOS 5D Mark II, digital and 35mm. Using two different cameras’ techniques and formats allowed me to bring more variety to the subjects I could choose, although I had to ensure enough consistency throughout.

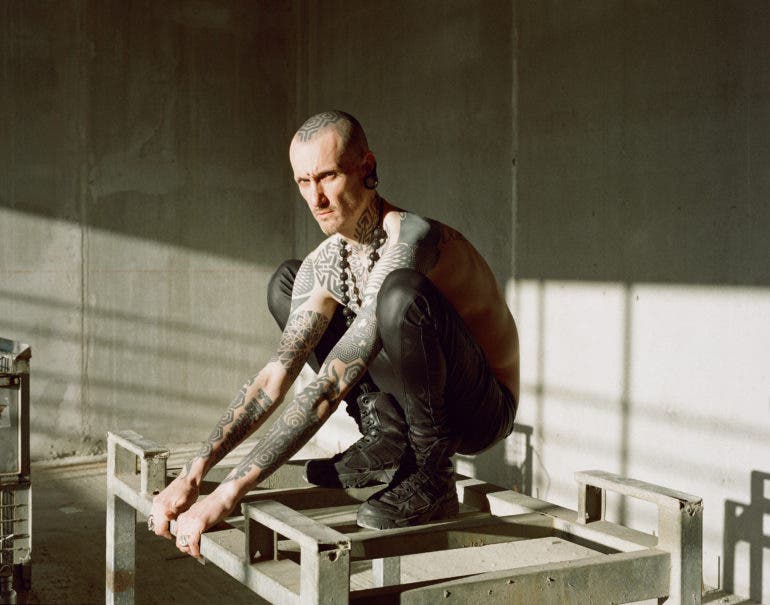

“Medium-format cameras have the great advantage of capturing details and textures more richly than a 35mm. I particularly enjoyed this higher resolution and very descriptive image when I started printing some of the photographs for the exhibition. In the print portraying Giacomo White Noise, for instance, you can see the skin texture and the tattoo pattern so vividly, it feels almost like real-life.

“Digital cameras, on the other hand, have their own sets of qualities. One that was useful to me is that they are better at capturing and freezing movement. When I photographed the dancer Rima Baransi, for instance, her body was in motion as she was performing for the camera, so digital was no doubt the best choice.

“We also wanted to use a location that somehow resembled Palestine, in line with Rima’s origins and her political militancy. We shot in a construction site with big long walls holding together huge dunes of sand, which are used in the production of concrete for a nearby tunnel. Having a lighter, hand-held camera meant, in this case, that I had better mobility and could try out different perspectives much quicker.

“In terms of lenses, I primarily used the Bronica Zenzanon-PE 75mm f/2.8 and Canon EF 50mm f/1.2 L USM, which offer an almost equal perspective across the different formats. I love this type of lens’ length because it’s the closest you can get to the perspective of the human eye. It makes it easier for me to compose the photograph looking straight at the subject in front of my eyes, without relying too much on the waist-level or viewfinder.”

Phoblographer: One of your portraits was recently named a runner-up in the All Out Photo Awards. In what way has the LBGTQ+ community helped shape your voice as an artist?

Gøneja: I owe so much to my LGBT+ communities in Berlin and London, where I used to live. Finding my people gave me the strength to stand up on my own feet and feel supported on my journey of self-discovery and growth. I wouldn’t have had the courage to take on an artistic path with photography had I not found them. They shaped who I am as a person and as an artist.

Phoblographer: How does it feel to have your work recognized by an organization like All Out?

Gøneja: It felt particularly meaningful as the scope of the Photo Award was not only the promotion of the artists per se but also the use of photography as a tool to keep the conversation on LGBT+ rights going. There are 69 countries with laws that criminalize homosexuality, let alone those where discrimination and hate are still deeply rooted, regardless of national policies.

Take, for instance, the recent events of homophobic violence in A Coruña, Spain, that led to the death of Samuel Luiz. There is much more work that needs to be done. Initiatives like these help make queer stories visible, while offering the artists who produce them a chance to reach a wider audience. I am so thankful to All Out for this opportunity and for all their work in general.

Phoblographer: Who are the people in Rituals, and what inspires you about them?

Gøneja: I tend to work primarily with people that I know personally; it’s important for me to establish a connection with my subjects. It’s also more interesting for me to operate within the boundaries of my community. It charges my work with an extra layer of meaning. Character is also important, and most of my portraits are shaped around this one component.

In Rituals, I continued to work with these parameters and focused on subjects with unique personal stories or interests. In the layout of the book, in fact, I decided to run their portraits alongside some of their own words, extracts from a text I asked each of them to write. Fadi, for example, talks about numerology as a form of wisdom that brought magic to his life and at times even shaped the direction of his path.

Phoblographer: Please tell us about your approach to portraiture, especially in the context of this book. Where did these shoots take place?

Gøneja: In Rituals, I wanted to frame each subject around a context that carried meaning for them. What you see in the book is not arbitrarily chosen; it belongs to the subject. Aga, for example, is portrayed with snakes wrapped around her naked body. We chose to shoot with these animals because of Aga’s fascination with these creatures, who came to represent some sort of mystical guidance in her life. I think it was precisely this approach that added that touch of rituality to the otherwise very classic type of portraits.

Locations were also very important, as sometimes they represented the context themselves. With Mart, for instance, we decided to travel to her grandmother’s town, a small village named Kolumna, in a remote corner of the Polish countryside. This is a place where Mart spent much of her childhood and one that shaped her introverted nature, so the location acquired a much deeper resonance. At the same time, I really enjoyed this approach: going in the middle of nowhere to make some portraits. It’s exciting for me to work with that level of commitment.

Phoblographer: Your sitters trusted you to photograph them nude and at their most vulnerable. Why do you think that is? How did you cultivate that trust?

Gøneja: I do not think that photographing people naked necessarily renders them vulnerable; the same experience can also be an empowering one. Take, for example, the way Vidadöd looks so glorious sitting on those huge rocks naked, only wearing her chunky platforms. We were both elevated to place her naked body against that otherworldly natural setting; it was a mystical situation for me.

Either way, what’s special for me about making nudes is precisely that trust and intimacy that is needed and that is inevitably embedded in the photographs themselves. It is also a very symbolic act: when a person is comfortable to take off their clothes to be photographed, it’s as if they’re removing all sorts of psychological layers and social constructs and they’re inviting you to look straight into their core-self.

It was definitively the case in the nudes I made with Pauline. Before we got to work, we had a little chat. I shaved her side hair, and we then decided to set the photographs in her bedroom. I’m grateful for that level of trust; it was a very intimate experience.

Phoblographer: Meev Eve contributed a piece of poetry/prose to the book, in which Berlin’s famous techno club Berghain–a safe space for LGBTQ+ people and allies–is mentioned as a kind of modern-day temple or church, where people can come together. What does the club represent to you?

Gøneja: The very idea for that text came about during a particularly inspired Berghain night Meev and I had in December 2019. It was the winter solstice; the sparkle of light in the midst of darkness managed to reach us. We didn’t know what the content of the text would be about, but we wanted it to touch upon some of the topics that we brought up that night in those uplifting conversations. I’m glad that the text captured so beautifully the rituality of that place: the early morning queuing procession, the healing sound of techno music, the hypnotic state of prolonged hours of dancing, and the sacrality of the whole experience.

Berghain is, to me, not only a safe place where I can be myself but also a sacred one where I found deep connections with incredible people and where I learned invaluable life lessons for which I am forever thankful. Having said that, this is also the place where Meev and I (and indeed all other subjects in the book) spent many great nights dancing our legs off to some truly epic techno sets–way too many to mention.

Phoblographer: Where do spirituality, mythology, and the occult fit into this book project and in your own life? And how does this spirituality tie into other themes explored in the book (e.g. community, identity, safe spaces)?

Gøneja: With Rituals, it was the first time that I felt I had enough maturity, spiritually and artistically, to explore those occult ideas with photography without banalizing them. Since then, I’m slowly realizing how spirituality is becoming the true calling of both my life and my work. The portfolio I’m working on right now is, in fact, taking that direction a step further.

How these overarching topics relate to my rather political position as a queer man, also explored in the work, is a rather big question. It’s as if my identity, community, and safe spaces are becoming the pretext for me to explore these larger, more philosophical questions. The queer world is not the message per se but the territory I use to explore spirituality, mythology, and the occult.

And by observing and reinterpreting in my photographic work how members of my community feel and relate to these questions, I can finally tell my own story and express my own truth. My message is thus bounded and interlaced with the stories that are available in my community and my artistic growth is even dependent on them.

To some, this position might be very suffocating, but to me, it’s actually a liberating one. Capitalist society has given us the illusion that we are enough on our own. But queer people more than others know that we depend on one another, our community, and our safe spaces. We know this as much as we know that our strength comes from standing together and working towards collective goals.

Phoblographer: Would you ever sit for a self-portrait or want to include yourself in the pages of this book?

Gøneja: I wouldn’t because that book and those photographs are already an expression of my inner self. A self-portrait wouldn’t be necessary.

Phoblographer: What is your most powerful memory from your time working on this book?

Gøneja: This project was the first time that I ever shot landscapes to the extent of traveling alone to remote corners of Europe, purely to photograph sites I spent weeks researching. As flights became available again after the first lockdown in Spring 2020, I ended up traveling to five different countries, one after the other, eventually visiting and photographing more sites than I decided to use in the final edit.

The last of them was an unusual concrete structure that stands in Montenegro, an abstract war memorial sitting on some hidden hills behind Podgorica, once the ground of a battle of Partisan resistance. I found myself once again taking off to a place I never been, reaching a neglected structure in a secluded setting, and waking up before dawn to be ready with my camera on location as the sun rose. This process alone felt like some sort of photographic pilgrimage.

That one trip also marked the last shoot for the Ritual series, as no more photography was planned, and the deadline of the book was approaching. As the daylight on the last shoot day ended, an unexpected ritual manifested. That evening in Podgorica, an explosion of familiar numbers and recurring symbols kept appearing synchronically everywhere I looked: on my phone’s clock, an overwhelming amount of car plates, random billboards, even on the shot count of my camera.

These signs helped me celebrate the end of this year and a half long project and reassured me I pushed things far enough. At that point, I was really ready to get back to Berlin, wrap this whole project up, and finally get it all out there.

Phoblographer: Your winning photo from the All Out Awards fell under this year’s Healing category. In what ways, if any, have working on this book served as a healing ritual for you personally?

Gøneja: This question touches upon another relevant point. The sudden and unexpected early outbreak of the pandemic was a very scary time for me. A lot of people in and outside queer communities struggled with mental health during those months. Chances to gather and share were few, and all places, including our safe spaces, were closing down, and most people around me felt empty and isolated.

For me personally, working towards the Rituals book and exhibition kept me sane and focused in the middle of that chaos and filled those days with purpose. It became a more positive narrative that helped me carry on and work through the adversities of the situation.

I was also very lucky that I had a chance to bring my community together for the book launch and exhibition opening, which went ahead in October 2020 as initially planned, right before the galleries had to close again. It was a very special moment for me. One of those nights that made all the efforts worthwhile, healed the struggles, and uplifted the spirit.

All photos by Gøneja. Used with permission. Learn more about Gøneja by visiting his website. You can follow along on Instagram at @goneja.