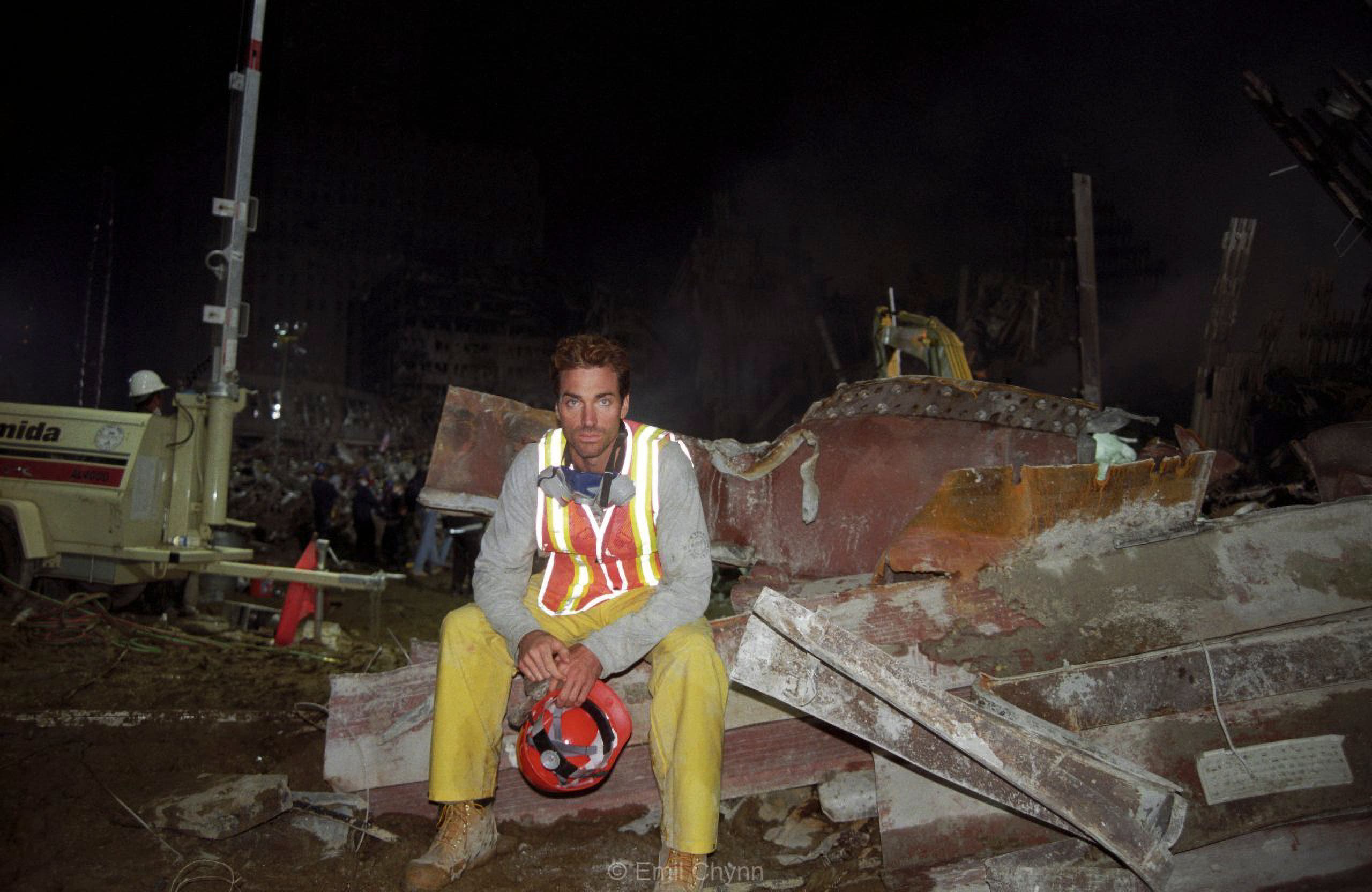

Dr. Emil Chynn Will Never Forget Being at Ground Zero on 9/11

We’re streaming daily on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, Pocket Casts, and Spotify! You can also listen to it right here on The Phoblographer.

“That day, I encountered literally thousands of people screaming and running past me in the opposite direction,” Dr. Emil Chynn remembers of September 11th, 2001. Two hijacked passenger planes had just been used in a coordinated terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, hitting the North Tower at 8:46 at the South Tower at 9:03. “Actually, I was the only person going downtown,” Dr. Chynn says. “I tried to flag a yellow cab to take me downtown, but nobody would stop. Finally, I got a cabbie to stop, but he said, ‘What are you, nuts? If you paid me a million dollars, I wouldn’t take you there!’”

Want to get your work featured? Here’s how to do it!

Dr. Chynn, now a well-known LASEK surgeon, was born and raised in New York City. That morning, he was out walking his dog, Hershey, when he saw the attacks happen. Determined to get downtown to help, he eventually put on his rollerblades and went to the World Trade Center by himself. He and a group of fellow medical professions set up a triage center in a Burger King at One Liberty Plaza. He would return to the site each day to volunteer for the rest of that week.

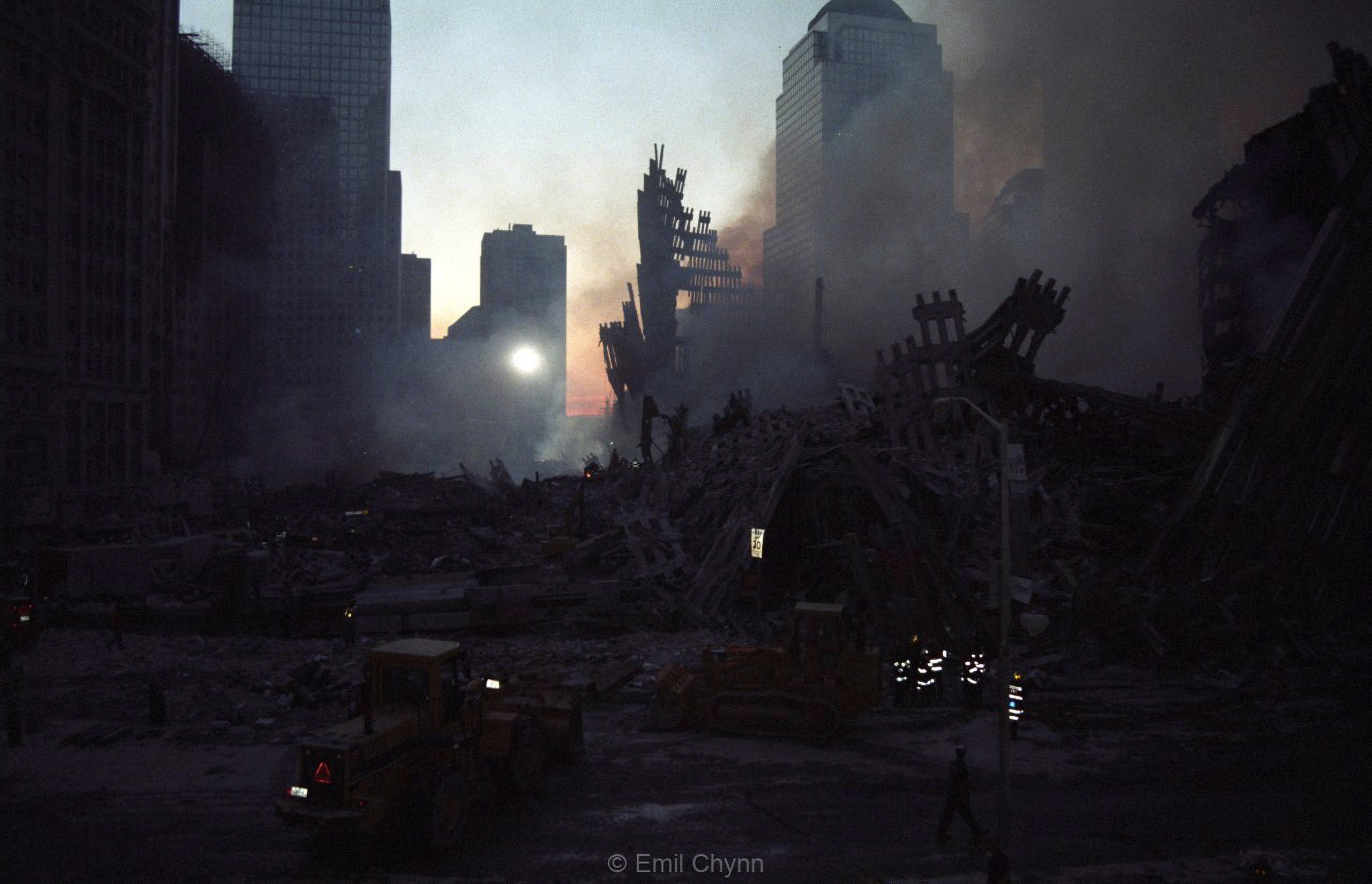

Though Dr. Chynn arrived as a doctor and a New Yorker first, he was also an amateur photographer. With his Nikon camera in hand, he would soon become a witness on the frontlines of one of the most traumatic events of our time on U.S. soil. “When I headed out from my apartment, both towers were still standing,” he tells me. “By the time I got downtown an hour later, it was very dark–like night. There was so much dust and debris in the air, and no electricity in the area. I was bumbling around with some other random volunteers for fifteen minutes, trying to find the Twin Towers.

“Finally, a construction worker in our group pointed to a small, maybe three- or four-story pile of debris, and said, ‘I think that’s one of the Towers.’ We all said he was crazy: ‘How could 100 floors get compacted into that small space?’ But after walking in circles for a few more minutes, we all finally realized that he was correct. And then it also hit us that there would probably be almost no survivors. You can’t pull victims from the debris when entire floors were atomized into the dust particles we were breathing in.”

We asked him more about that day.

Phoblographer: You were one of the first doctors on the scene. What motivated you to go there on that morning and return in the days following? Was there any hesitation?

Dr. Emil Chynn: A decade prior, I was an intern at the closest major hospital when WTC was attacked the first time. Most people don’t know this, but a terrorist detonated a truck bomb in the underground garage. The house staff were all asked to not go home (even though we had all been working 12 to 24 hours already), so we all stayed. However, it took three hours for the first victims to arrive because of delays in on-site triage and transportation. So when I saw the Twin Towers burning from my apartment a few miles uptown in the West Village, I decided to go down to the scene, thinking that I would be more useful immediately helping with triage, given my prior experiences.

Phoblographer: What is your most indelible memory from that week, 20 years on?

Dr. Emil Chynn: The greatest fear was on that first day, 9/11 itself. Once I got below Worth Street, there was too much debris on the ground to continue, so I hid my rollerblades in an abandoned burnt-out fire truck and continued on foot. That heightened my anxiety because you usually think, “Once the firemen arrive, everything will be okay” So it was really scary seeing a big fire truck that had been destroyed by falling, burning debris, and abandoned.

A few blocks further south, I encountered a burnt-out police car and a destroyed FBI car. Same strange feeling. In medicine, we call this the “feeling of impending doom.” It’s basically your autonomic nervous system warning you, telling you that something bad is happening, that you are at grave risk, and you should get the fuck out of dodge. Seeing firefighters, FBI “G-men,” and NYPD cops stumbling around stunned, sitting on curbs numb, and some crying certainly didn’t help.

It was total chaos. Like a war zone. Nobody in charge. I think the Marines call things like this “FUBAR”: “fucked up beyond all repair.” Not something I ever thought I would personally experience. Especially not in the middle of New York City, only a couple of miles from my apartment. The incongruence of this made it even more disorienting and disturbing. You have to understand that there was absolutely no “organization,” or I guess what would be called “command and control” down there that day. How could there be? Nobody had anticipated a huge terrorist attack on American soil before this.

At one point, I remember talking to the Mayor’s Office, and they were asking me what supplies I would need, and I kind of blanked out for a minute and forgot what they taught me about IV solutions for trauma and blood loss, versus rehydration. D5W? Normal saline? And what the fuck is “Ringer’s lactate” supposed to be used for again?! Who would want to be under that kind of inordinate pressure? Nobody. It’s a scary, stifling, traumatic, heartbreaking experience.

Phoblographer: How did you cope with your own fear on the days you were working triage?

Dr. Emil Chynn: I seem to have an unusual ability to “get my shit together” in bad situations and not let my emotions affect my actions or ability to think clearly. Probably some of this is learned, and something you have to acquire as a surgeon, because every surgeon will run into some unexpected calamity in the OR at some point. But on 9/11, I was only an intern, fresh out of medical school at Columbia, and hadn’t started my eye surgery training yet. So I guess some of this ability must be innate, as well.

I remember on day two or three, which would be 9/12 or 9/13, I was interviewed by ABC or NBC, and got a call from my ex-girlfriend, Melanie, from Boston. She said, “I was in the kitchen, the TV was on, they were interviewing ‘the first doctor at Ground Zero,’ and I heard your voice, and I knew it was you.” I said, “Why, because I have such a distinctive voice?” She replied, “No–because I know you, and only you would be crazy enough to do something like that.”

Phoblographer: What made you bring your camera?

Dr. Emil Chynn: At that time, I was a serious amateur photographer. I didn’t bring my camera the first time I headed downtown. It was only when I went back to my apartment to get my rollerblades that I decided to grab it. I was shooting film at that time–everyone was.

I had a Nikon, but I forgot which model, and probably put on my Tamron 35mm-150mm zoom or something like that. I can’t remember what film I was shooting, but I do know that it was mostly for prints, not slides. I also remember the first day wishing I had faster film speed, like 400 ASA or higher, because it was so dark because of the debris.

Phoblographer: Was there anything or anyone you chose not to photograph?

Dr. Emil Chynn: Well, I made a conscious decision to not photograph any body parts, out of respect for the dead. Actually, I initially did that, once, but then I felt bad and kind of guilty and shameful, so opened up my camera back and destroyed the negative.

Phoblographer: Were there any moments or interactions amid the horror of what you witnessed that gave you hope?

Dr. Emil Chynn: Everyone down there that day was, by definition, a hero. When I was setting up the first triage center at Burger King, I told the Mayor’s Office and the Battalion Commander that they couldn’t send any ambulances because the streets were literally knee-deep in debris, so they wouldn’t be able to get through.

A guy standing next to me in a hard hat overheard my conversation, and said, “Hey, doc, just tell me whatever you need, and you got it.” He then ran over to a nearby construction site, hot-wired a backhoe, and started literally plowing the streets of debris, like using a snowplow. I later found out he worked for NYC Sanitation, and like me, had decided to head downtown when he saw the Towers on fire. So there were certainly a lot of unsung heroes that day–including that gentleman.

I think also about a young blonde nurse in her 20s who was with us looking for the Twin Towers right after they fell. Can you imagine her deciding to go downtown when she saw the towers on fire? Unbelievable. I regret that we volunteers never had time, nor thought of exchanging contact information, but I sometimes wonder what became of her. She would be in her 40s now. I’m still single, so I don’t have kids of my own yet, but I sometimes wonder what her kids are doing now–probably something amazing, with a parent like that.

Phoblographer: Are you in touch with any of the other healthcare workers who set up the triage center with you? What do you remember most about them in the aftermath?

Dr. Emil Chynn: Some of us used to have annual gatherings like a dinner near what was WTC around the anniversary of 9/11, but unfortunately, after maybe five years, whoever was organizing that stopped, and we all lost touch. If anyone out there is enterprising and energetic, I would love it if someone would set up a website where anyone who was at Ground Zero from 9/11 through 9/30 could register, and then maybe we could all hold annual gatherings. I think it could be therapeutic, cathartic, and beautiful in some way.

Over the course of the week that I volunteered on “The Pile,” which is what people down there had started calling the mound of debris, I met dozens of brave and wonderful healthcare workers–nurses, medical students, EMTs, PTs, OTs, and of course other doctors. The beauty of so many people working together, selflessly, was exactly the salve that we all needed to feel, to heal us from the trauma we had witnessed, caused by one of the most heinous acts in US history.

It would have been so easy for any of us to “turn to the dark side.” I did see some graffiti down there, saying things like,” Let’s Bomb Them Back to the Dark Ages!” So it was very important to also simultaneously witness the very best acts of kindness and generosity that humans are capable of.

Phoblographer: Could you tell us the story of one of the people you treated? What makes this person stand out in your memory?

Dr. Emil Chynn: I would like it if I could provide an uplifting story of somebody who was pulled out of the wreckage, and then we got to “save” that person. There were a few stories like that, but unfortunately, most of them were just that–stories. I myself didn’t see one survivor the entire time I was there, which was most of the first week (I went home for about five hours per night to shower and change and nap). So a huge challenge for the medical workers there was to keep their spirits up, despite no “success.” Eventually, we tried to take solace from treating injured volunteers and cops and firefighters.

Phoblographer: How long did you wait before publicly releasing these photos?

Dr. Emil Chynn: They were first exhibited in an exhibit in NYC downtown called Here is New York. Most of the interest is in the very earliest photos, as they are among the very earliest photos taken by anyone at Ground Zero because the media wasn’t allowed below Canal Street that day. Last year, I got interviewed by some European newspapers for being the first doctor at Ground Zero, and was told by some European friends that they saw them, so I guess they have been seen around the world.

Phoblographer: Are you still a photographer?

Dr. Emil Chynn: I got into photography because of my dad, who taught me how to develop and print black and white. He died under tragic circumstances last year. I wasn’t allowed to be with him at his death and wasn’t even initially told that he had died. I’m still very upset about that. I bought a mirrorless DSLR (Sony) a few months ago to cheer myself up, but have only used it once. I’m suffering from what’s called anhedonia, and am in protracted bereavement. Hopefully, once these bad things end, I will be able to take up hobbies again, including photography.

Phoblographer: Are these photographs very painful for you to look at today, or have they helped you to cope with the trauma of what you saw? Both?

Dr. Emil Chynn: I wouldn’t say the photos are painful or traumatic. They’re more like looking at a part of my life–here’s my First Holy Communion, high school graduation, graduation from Dartmouth and then Columbia, and then WTC. It’s probably been formative in my life; I just don’t realize it.

Only people who have experienced similar things, like in a war zone or disaster area, truly can understand what something like this does to you. They say it takes a great event to make a great man. I don’t have enough hubris to say that I am “great.” But after having lived and suffered and overcome at Ground Zero on 9/11, at least on that day I learned who I was–a man who would never run away from adversity due to fear, but would head towards danger to protect the ones I love.

Dr. Chynn will be hosting a benefit with his certified Service and Therapy dog, Tolstoy, on Saturday, September 11th, from 11:00 AM to 3:00 PM on Cornelia Street in New York’s West Village. “I’d like to help people view 9/11 as a call for global harmony, so we decided to choose the 9/11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows as our charity this year,” he says. There will be food, drinks, and entertainment, and for every time a guest donates to the charity, Park Avenue LASEK will give them twice that amount off LASEK, up to donations of $2,000. Their goal is to raise more than $10,000.

All photos by Dr. Emil Chynn. Used with permission. For more from Dr. Chynn, visit his website and his 9/11 photo gallery. You can follow along on Instagram at ParkAvenueLASEK and on Facebook at ParkAvenueLASEK.