How Landscape Photographers Reinvented the Colonial Project in Australia

Colonial history overflows with commodities. From the early 1800s, wool generated extraordinary wealth for squatters and pastoralists and substantial investment in the Australian colonies. In the 1850s, gold motivated tens of thousands of people to work the earth or service the diggings. Coal, copper, tin, wheat, barley, and cotton all assumed importance at different times.

In those great cathedrals of late 19th-century colonial self-representation, the International Exhibitions, any visitor would have immediately noticed the way New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania sought to identify with the commodities produced in these places.

In a photograph from 1879, the NSW Department of Mines filled its portion of the exhibition building, the Garden Palace, with gold ingots, silver ores, and samples of tin. On the balconies above were coal sections and geological maps.

Walking through these displays a visitor would also have noticed walls of landscape photographs, which, mirroring the extractive logic of settler colonialism itself, worked to bring all these raw materials together in a vision of abundant nature.

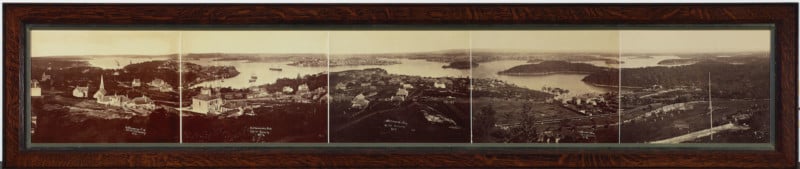

Photographers captured images of budding settlements, seemingly empty vistas, and stunning panoramas of emerging colonial cities.

The increasing popularity of these photographs throughout the final decades of the 19th century shows colonial expansion was not just generated by the search for raw materials to extract and exploit. Colonial Australia was also a product of vision and imagery: literally developed through chemicals, glass, and light.

I have studied over 2000 early landscape photographs, taken by six settler photographers between the 1850s and the 1930s. They show how colonization was re-enacted in the imagination of places, rather than simply through the movement of people from one site to another, the Lockean mixture of labor and earth, or the transfer of deeds.

Visions of nature allowed for a different kind of investment in the colonial earth. They paid off in feelings of belonging even for those who never turned a sod. These photos reveal, as the American environmental historian William Cronon has insisted, that nature itself is a profoundly human artifact.

In settler colonies, landscape photography framed nature as beautiful, available and empty. In Victoria and Tasmania especially, landscape photography flourished. And although this mode of photography was not uniquely antipodean – it was pioneered, then perfected in the American West by photographers like Carleton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge – it did have remarkable purchase in the Australian colonies.

A Photographic Sleight of Hand

Figures such as Nicholas Caire, John Lindt, and John Beattie took up the camera to encourage settlers to feel at home in Australian environments. This perspective disguised the ancestral ownership and continuing presence of First Nations peoples, turning their homelands into a wilderness through a photographic sleight of hand.

The best example of this was in Victoria, where Caire and Lindt began framing the stretch of bush between Healesville and Narbethong as a kind of wilderness retreat from the late 1870s.

Caire, born in Guernsey in 1837, came to this collaborative work via South Australia, the forests of Gippsland, and the Goldfields. Lindt, originally from Frankfurt, had just finished photographing Bundjalung and Gumbaynggir people along the Clarence River in northern NSW.

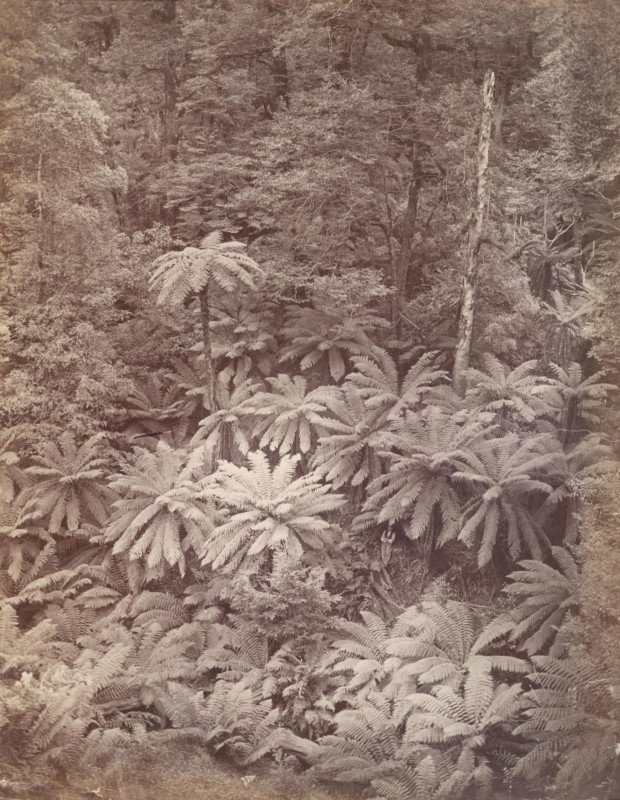

Around 1878 Caire captured Fairy Scene at the Landslip, Blacks’ Spur, which quickly became one of his most popular photographs.

In it, Caire focuses on a glade of tree-ferns clustered on the side of a gully. Writing in 1904, Caire and Lindt boasted about the wildness of this pocket of the Great Forest, the ancient age of the trees, and the “refreshing” seclusion of Fernshaw. Lindt wrote that the allure of places like this came back to their capacity to “carry you back to the morning of time”.

The empty natures of the Yarra Ranges relied on the removal and containment of Woiwurrung, Bunurong, and Taungurong people at the Coranderrk mission. Located just kilometers away from Lindt and Caire’s “refreshing” forest, Coranderrk helped the photographers create a partition between the environment and its ancestral owners.

The mission became a complementary site of interest. When promoting the natural features of the Yarra Ranges, Lindt and Caire wrote about Coranderrk as a place where tourists could mimic the anthropologist, just as they mimicked the geographer or explorer while traipsing through sylvan glades or gazing up at giant mountain ash.

At about the same time that Caire and Lindt were developing their visions of nature in the Yarra Ranges, the photographer Fred Kruger was taking influential shots of life on the reservation. One of the key challenges for aspiring landscape photographers in the 1870s and 1880s was to deal with this presence of Aboriginal people in landscapes that were becoming coveted for their natural beauty.

Caire and Lindt took up an established tradition of photography at Coranderrk, combining it with a new interest in wilderness, balancing the apparent contradiction between Indigenous presence and absence.

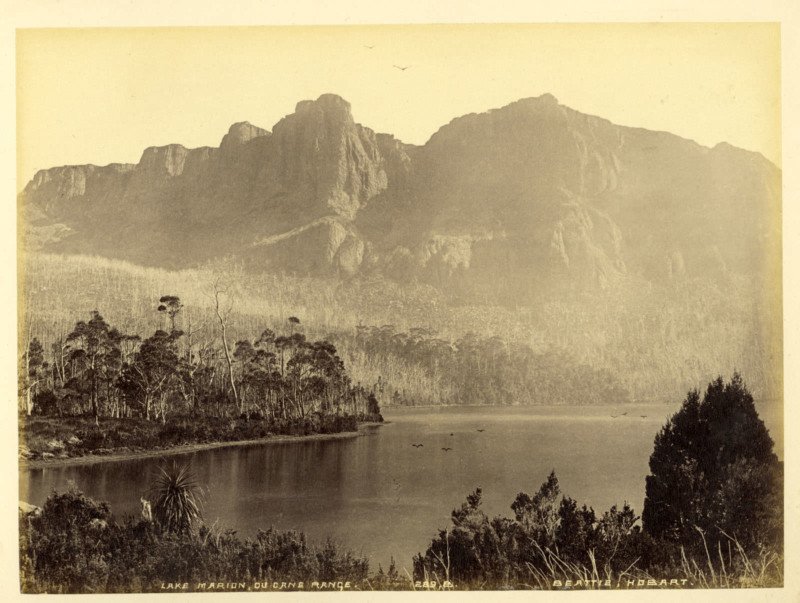

The Tasmanian Sublime

In Tasmania, too, photographers began constructing a similar wilderness tradition from the 1870s. Emigrating from Scotland in 1878, John Beattie, the so-called “prince of landscape photographers in Australasia”, settled with his family in New Norfolk, about 30 kilometers up the Derwent valley from Hobart.

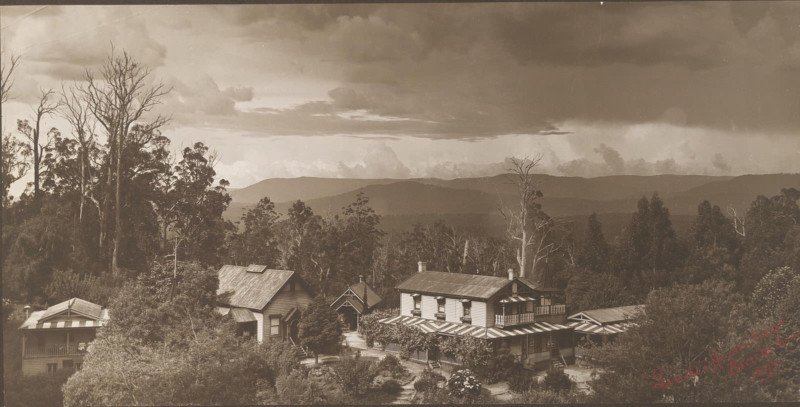

This was a perfect location for a budding photographer, and Beattie made attractive pictures of the river and its hop gardens in the 1890s, but the interior of the island offered a different order of beauty.

In 1879 Beattie began making expeditions into the bush around the valley, onto the central highlands, and eventually all the way to the remote Lake St. Clair. In 1882 he joined the Anson Brothers’ photographic studio and quickly became their most important artist.

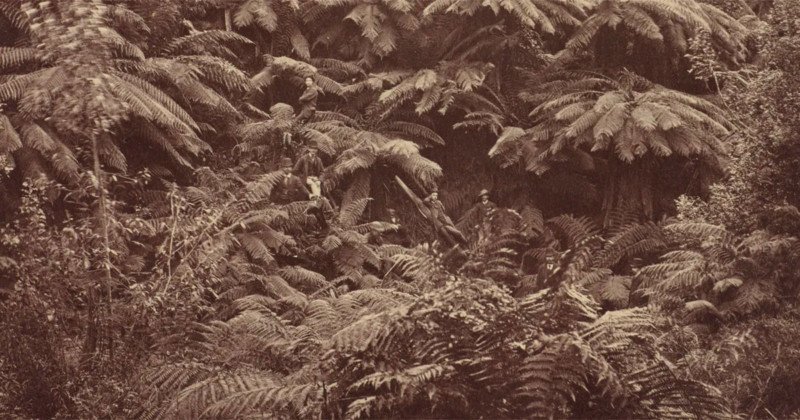

An Anson Brothers image from 1887 is quite likely Beattie’s work, showing a stand of ferns on the Huon Road. Unlike Caire’s shot, however, this image includes a group of settlers enjoying exactly the kind of immersion in nature that these photographs were designed to evoke.

Many of Beattie’s photographs are deeply Romantic. Between 1896 and 1906 he conducted regular presentations in Hobart and Launceston based on the wild features of the Tasmanian landscape, cultivating a high wilderness aesthetic in his magic lantern shows.

Photographs of Lake Marion and the Du Cane Range and another of Lake Perry and The Pinnacles trade in the sublime. Beattie evoked the great American transcendentalist poets in his respect for the mountaintop, which often moved him to wordlessness: “I am struck dumb, but oh! my soul sings.”

These sublime sentiments relied on old Romantic ideas that stretched back to Edmund Burke and William Wordsworth, but they rested just as heavily on new experiences of space. Beattie’s breakthrough years were in the 1890s, a decade in which depictions of wilderness in Australian Romantic painting went into terminal decline and were replaced by photographic visions of nature.

Romanticism, through photography, came to influence how environments were envisioned and how histories of dispossession were remembered. The high wilderness imagery of settler photography came to support a fantasy of spatial control, delivering reproducible, enduring symbols of the natural world.

Aboriginal Extinction and Romantic Communion

Just as Caire did, Beattie divided his visions of nature and his portraits of native people. He was an insatiable and opportunistic collector of photographs of the “last” Tasmanians, leaning into and commercializing the myth of Tasmanian Aboriginal extinction.

Sometimes advertisements for these pictures featured on the back covers of Beattie’s landscape collections, gently leading interested audiences to the other side of the partition.

Most of Beattie’s photographs of Aboriginal people were simple reproductions of the portraits that Francis Nixon, the first Bishop of Tasmania and amateur photographer, took in 1858 at putalina (Oyster Cove). Nixon took pictures of the few remaining Aboriginal people, who had survived exile on Wybelenna Station on Flinders Island and a decade of surveillance at the former penal probation station just south of Hobart.

In the 1890s Beattie copied these images and labeled each of them with the phrase “the last of the race”.

It is no simple coincidence that this language was adopted by one of Australasia’s most successful landscape photographers. Aboriginal extinction and Romantic communion with the wilderness were the twin fantasies that shaped settler visions of nature in the late 19th century.

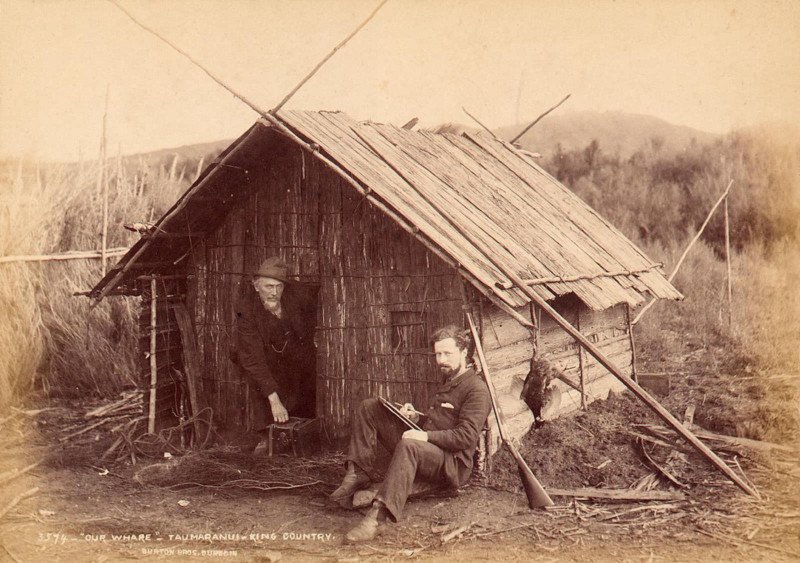

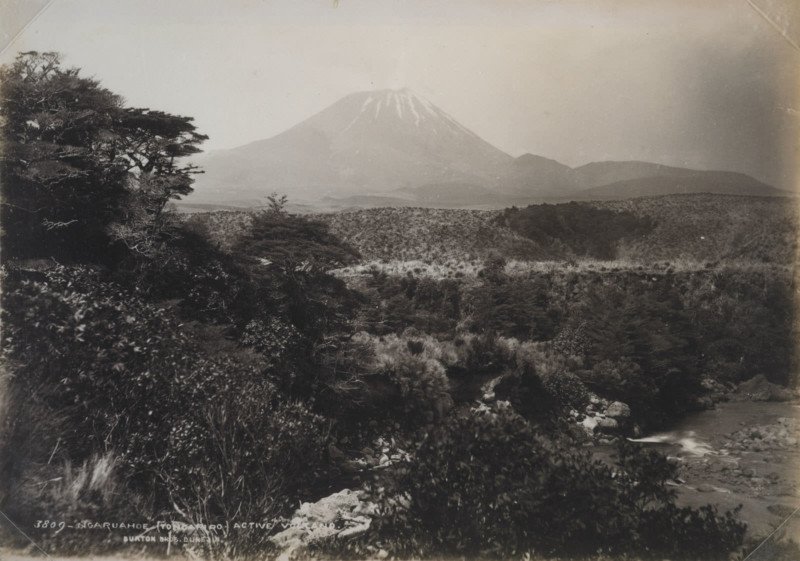

This dynamic influenced landscape photography well beyond the Australian colonies. Across the Tasman in New Zealand, the Dunedin photographer Alfred Burton became famous for an 1885 album called The Maori at Home, which delicately balanced ethnographic and wilderness imagery, much as Caire did.

Burton used the camera to carve the local Māori from their ancestral homes, creating a “terra incognita”. He created visual partitions between the traditional custodians, Ngāti Maniopoto, and the landscapes of the Waikato and divided the people of Ngāti Tūwharetoa from the monumental geography around Tongariro, Ngāuruhoe, and Ruapehu.

Burton and a party of adventurers returned a year later, in 1886, to immerse themselves more fully in these sublime environments. More settlers would follow in Burton’s footsteps from the mid-1890s, when, after a long struggle with Ngāti Tūwharetoa, the heights around Tongariro became New Zealand’s first national park.

The same kind of processes shaped settler attitudes to one of the United States’ most famous national parks, Yosemite, where photographers like Watkins and Muybridge erected similar partitions between their natural and human subjects.

This division was spectacularly represented in a set of photographs that used the still waters of Yosemite’s reflective lakes to capture stunning landmarks. In these works, the myth of empty wilderness was turned into the beautiful motif of a glassy lake.

We might expect that Caire, Beattie, and Burton consciously adopted this technique from their American kin but there is no evidence this was the case.

Control Over Land

It’s more likely that comparable visions of nature developed in parallel, drawing from similar histories of dispossession and environmental transformation in different settler colonies.

In a whole range of places where pastoralists failed to graze their herds and geologists struggled to identify economic deposits, photographers helped colonists continue the cultural work of establishing dominion over stolen land.

The earliest visions of nature in Australia perfectly captured this drive, fixing its orientation to the physical world and its settler colonial history onto glass negatives, lantern slides, and paper cards.

And here is where the commodities come back into the story. Settlers adopted the holistic vision of landscape photography to exert control over land. Figures like Caire and Beattie perfected a kind of environmental image-making and storytelling that encouraged settlers to feel an affinity with the natural world.

Their customers were drawn to breathe in the highly oxygenated forest air or pursue the Romantic thrill of summiting a mountain. These experiences became a commodity in and of themselves, and so did the photographs documenting them. They adorned sitting rooms, galleries, and exhibition halls – summoning memories and lending a new assurance to the settler enterprise.

Jarrod Hore’s book, Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism, is available for pre-order now.

About the author: Jarrod Hore is Co-Director and Postdoctoral Fellow of the New Earth Histories Research Program at the University of New South Wales. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.