Malicious Chrome and Edge add-ons had a novel way to hide on 3 million devices

In December, Ars reported that as many as 3 million people had been infected by Chrome and Edge browser extensions that stole personal data and redirected users to ad or phishing sites. Now, the researchers who discovered the scam have revealed the lengths the extension developers took to hide their nefarious deeds.

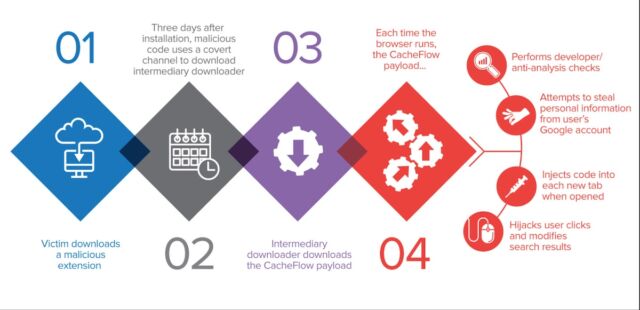

As previously reported, the 28 extensions available in official Google and Microsoft repositories advertised themselves as a way to download pictures, videos, or other content from sites including Facebook, Instagram, Vimeo, and Spotify. Behind the scenes, they also collected user’s birth dates, email addresses, and device information and redirected clicks and search results to malicious sites. Google and Microsoft eventually removed the extensions.

Researchers from Prague-based Avast said on Wednesday that the extension developers employed a novel way to hide malicious traffic sent between infected devices and the command and control servers they connected to. Specifically, the extensions funneled commands into the cache-control headers of traffic that was camouflaged to appear as data related to Google analytics, which websites use to measure visitor interactions.

Referring to the campaign as CacheFlow, Avast researchers wrote:

CacheFlow was notable in particular for the way that the malicious extensions would try to hide their command and control traffic in a covert channel using the Cache-Control HTTP header of their analytics requests. We believe this is a new technique. In addition, it appears to us that the Google Analytics-style traffic was added not just to hide the malicious commands, but that the extension authors were also interested in the analytics requests themselves. We believe they tried to solve two problems, command and control and getting analytics information, with one solution.

The extensions, Avast explained, sent what appeared to be standard Google analytics requests to https://stats.script-protection[.]com/__utm.gif. The attacker server would then respond with a specially formed Cache-Control header, which the client would then decrypt, parse, and execute.

The extension developers used other methods to cover their tracks, including:

- Avoiding infecting users who were likely to be Web developers or researchers. The developers did this by examining the extensions the users already had installed and checking if the user accessed locally hosted websites. Additionally, in the event that an extension detected that the browser developer tools were opened, it would quickly deactivate its malicious functionality.

- Waiting three days after infection to activate malicious functionality.

- Checking every Google search query a user made. In the event a query inquired about a server the extensions used for command and control, the extensions would immediately cease their malicious activity.

Here’s an overview of how the extensions worked:

Based on user reviews of some of the extensions, the CacheFlow campaign appears to have been active since October 2017. Avast said that the stealth measures it uncovered may explain why the campaign went undetected for so long.

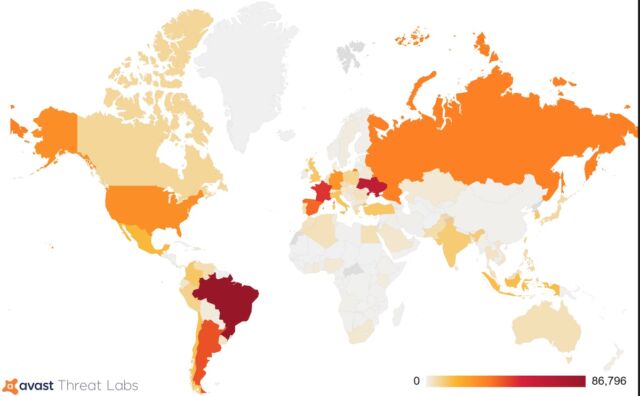

The countries with the largest number of infected users were Brazil, Ukraine, and France.

Ars’ previous coverage lists the names of all 28 extensions found to be malicious. Wednesday’s Avast follow-up provides additional indicators of compromise that people can check to see if they were infected.